Apalachicola History

Black History Trail

Learn about the people and places important to Apalachicola’s Black History. Visit the online Black History Trail and learn more about each location by clicking here.

Apalachicola is one of the most historic cities in Florida. Located where the Apalachicola River meets Apalachicola Bay, the name “Apalachicola” is an Indian word interpreted as a ridge of earth produced by sweeping the ground in preparation for a council or peace fire. Over time, the term has been translated as an area of peaceful people or people on the other side. “Land of the friendly people” is a common interpretation of the word.

But even before the city was founded, the area surrounding Apalachicola was an important center of history. Remnants of native American cultures date back to the Middle Archaic period (2000 BCE) and documentation exists that claims native cultures have lived here during the intervening Woodland and Mississippian periods. Archaeologists estimate that the population could have reached 40,000, attracted to the area due to stable water supplies and abundant game. Middens left by these settlers are composed primarily of clam and oyster shells. Some of the larger middens were used as burial sites.

Europeans first explored Franklin County in the early 1500s as Panfildo de Narvaez visited a location near present-day Apalachicola. The journal of his expedition describes a coastal island that is believed to be Dog Island, St. Vincent Island, or St. George Island. The earliest-known European settlement of the area was a fort built at the mouth of the Apalachicola River by the Spanish in 1705 where it remained under Spanish ownership until it was ceded to England in 1763.

In 1783 the area returned to Spanish control after the Second Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War. Some British trading companies, including Panton, Leslie, and Company were allowed to remain. In 1811, the trading company John Forbes and Company persuaded Spain and the Indians to cede 1.5 million acres between the Apalachicola and St. Marks Rivers to their firm because of large debts owed to their trading company by trader Indians. The transfer became known as the Forbes Purchase.

Because of unrest in its more populous colonies in Central and South America, Spain was unable to effectively control Florida. In 1818 the U.S. army attacked Indians living in Spanish Florida in what became known as the First Seminole War. Spain ceded Florida to the United States in 1821. In 1828 the town which was originally named Cottonton was incorporated as West Point and later renamed Apalachicola in 1831.

Industries Through the Years

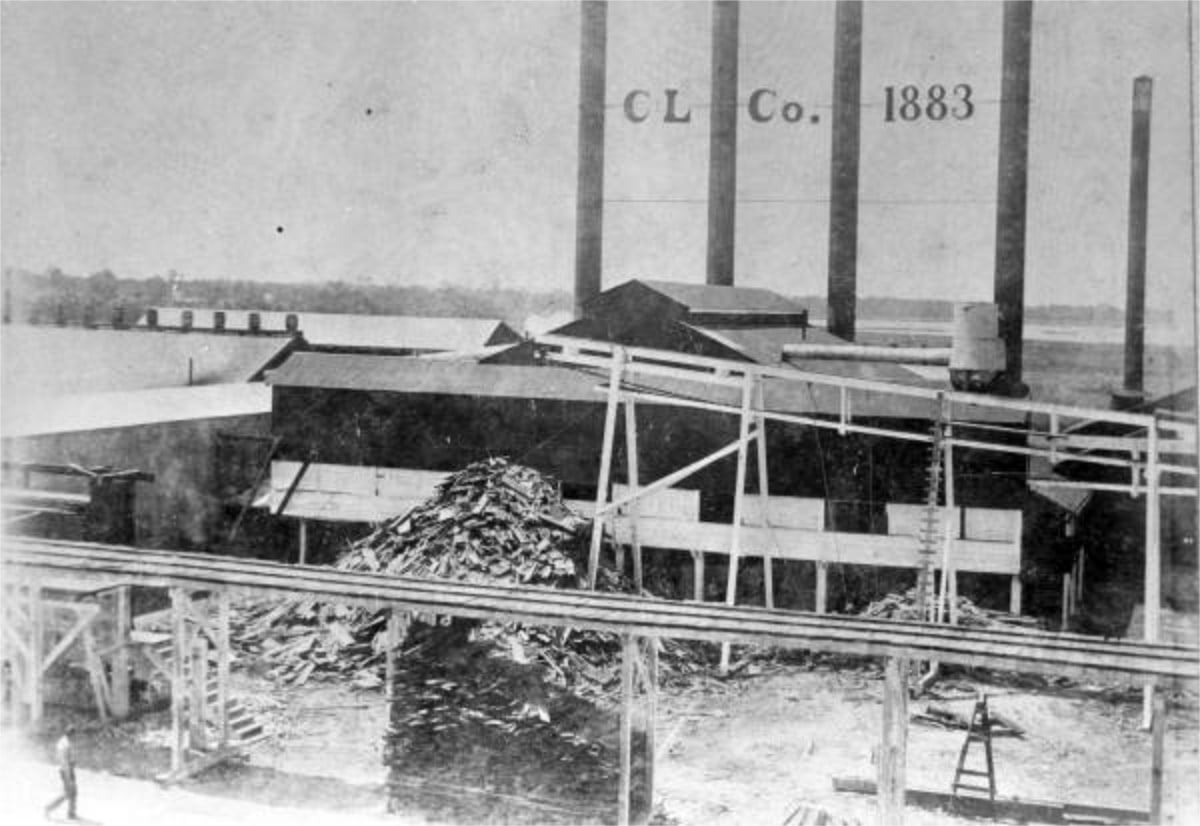

Timber Industry

Ferris, G. A. Cypress Lumber Company building in Apalachicola, Florida. 1896. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory.

Apalachicola's timber industry emerged prior to the Civil War alongside a booming cotton shipping trade. One of the town's first sawmills, the Pennsylvania Tie Company, was located at a site known today as the “Mill Pond” or Scipio Creek Boat Basin on North Market Street. The sawmill cut railroad crossties from cypress logs that had been dragged from the swamps surrounding the Apalachicola River.

Despite an abundance of timber, early efforts to expand the industry were thwarted by high transportation costs, under-capitalization and the ever-present industry hazard of fire. It wasn’t until James N. Coombs came to Apalachicola in the late 1870s when, backed by Northern capital, Coombs went on to establish and manage several sawmills in the county. Other mills followed including the Cypress Lumber Company, Franklin County Lumber Company and Kimball Lumber Company.

Spurred on by a worldwide demand for timber products, sawmills soon sprang up along the river, and millions of board feet of pine and cypress passed through the port of Apalachicola. Pines were also sought for their sap, which was distilled into turpentine and resin and known collectively as naval stores.

Close-up view of log rafts in a log boom at Apalachicola, Florida. 1899. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory.

By the end of the 19th century, billions of feet of longleaf yellow pine, as well as ash, cypress, poplar, cottonwood, sweet gum and tupelo gum were harvested from throughout the region, cut and shipped upriver by paddlewheel steamboat or ferried by shallow-draft lighters to larger ships waiting offshore for shipment to Europe and Mexico. The timber industry meant a large increase in traffic on the Apalachicola River. The commerce of the river system went from $2,000,000 in 1898 to $13,324,000 in 1903.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the capacity of the local mills was greater than the area’s shipping facilities and it became clear that a faster more efficient means for shipping lumber was necessary in order for the industry to grow. Relief arrived in 1903, when the Apalachicola Northern Railroad rolled into town and with it the promise of faster and more efficient shipping.

Apalachicola’s timber industry flourished until the mid 1920s, declining, in part due to dwindling virgin timber stands and a declining naval stores industry.

The Sheip Lumber Company

The Sheip Lumber Company occupied a site beside Scipio Creek at the north end of Market Street. This property has been the site of a sawmill for many years, stretching back before the Civil War. Thomas Hutchinson reportedly had a sawmill on this site that was destroyed by the 1851 hurricane that struck Apalachicola.

After the Civil War Col. Archibald B. Tripler built the Pennsylvania Tie Company mill on this site to saw railroad ties. After going bankrupt the mill passed through several hands before being purchased by the Central Florida Mill and Lumber Company in 1880. Three years later this company sold out to Albert T. Stearns of Boston, Mass. who organized the Cypress Lumber Company. This company operated for over 40 years before selling the mill to the Sheip Lumber Company.

Jerome Sheip, the owner of the Sheip Lumber Company was born in Pennsylvania in 1862, and engaged in the lumber business his entire life. He started out producing cigar boxes in Philadelphia and expanded into other aspects of the business. When he purchased the mill in Apalachicola in 1926 the plan was to manufacture cigar box lumber exclusively. By 1940 the mill was also cutting lumber for furniture. At that time the foremen for the various departments at the mill were C. J. Brass, sawmill; R. W. Stewart, planing; W. J. Norred, finishing department; Mr. Mayson, power plant; J. H. Hildreth, chief engineer; and A. V. Thigpen, yard and dry kiln. H. M. Brown was the sawyer at the mill. Over 200 men were employed at the mill.

The mill operated into the late 1940s. Jerome Sheip died in 1952 in Apalachicola. The property was subsequently deeded to the City of Apalachicola where today it serves as the City’s commercial boat basin.

Apalachicola Railroad Era

Apalachicola’s first railroad engine steamed into town on April 30, 1907 amid a town-wide celebration. The Apalachicola Northern Railroad (ANR) tracks entered town at the north end of Market Street and ran parallel along Water Street to its terminus at the Railroad Depot located near Commerce Street and Avenue G. A spur of the rail line extended to the south end of Water Street to load seafood from the packing houses on the river.

Crowds greet arrival of first Apalachicola Northern Railroad company train - Apalachicola, Florida. 1907. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory.

The emergence of railroads to North Florida in the mid 1830s was propelled, in part, by a need for more reliable shipping alternatives. Steamboats ruled the river during the early to mid 1800s but were not always reliable, hindered constantly by unpredictable river levels, snags and mechanical problems.

The first efforts to establish rail travel to the area began many years before the effort was successful. In 1885, a group of Apalachicola businessmen secured a charter for the Apalachicola and Alabama Railroad Company. The group hoped to build a rail line northward to connect to the Pensacola and Atlantic Railroad network in Jackson County. Unable to secure financial backing for the endeavor, the rail plan was abandoned until 1903, when North Florida businessman Charles B. Duff and partners chartered the Apalachicola Northern Railroad (ANR). Construction began in 1905 and trains began running north from Apalachicola in 1907. From Apalachicola, the ANR route ran north of Apalachicola to Chattahoochee where an interchange was made with the Atlantic coast Line. An extension to Port St. Joe was completed in 1910.

Rail commerce flourished in the area until the timber resources started to dwindle in the 1920s. In 1933, the railroad was purchased by Alred I. duPont to service the St. Joe Paper Company mill in Port St. Joe which operated there from 1936 to 1996.

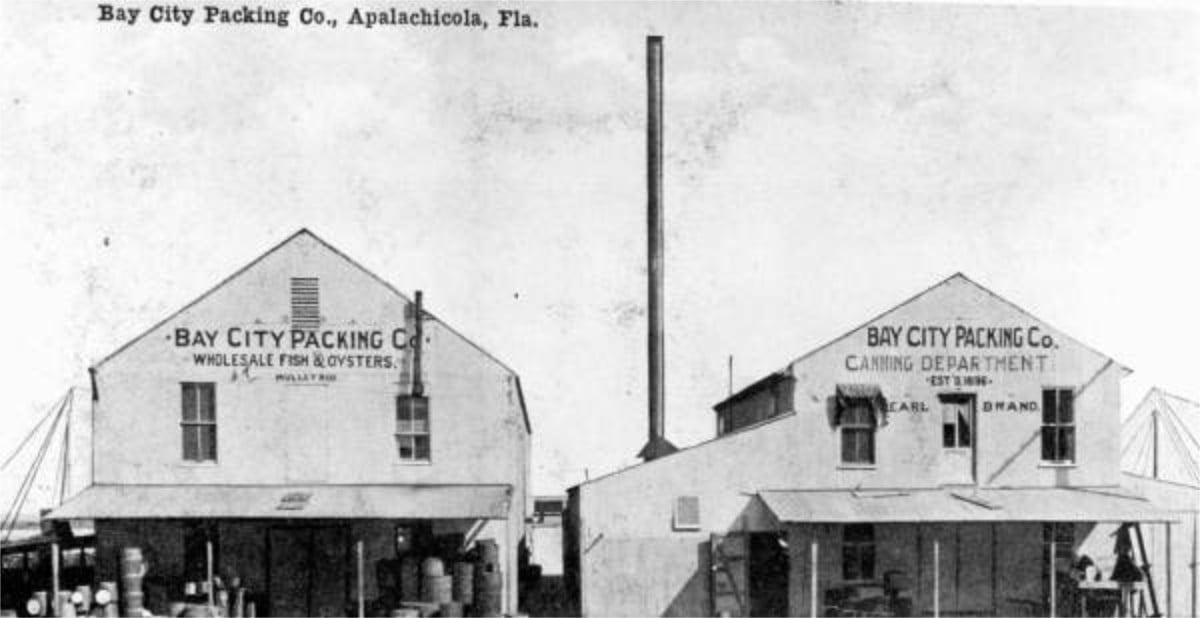

Apalachicola’s Early Seafood Industry

Man gathering oysters - Apalachicola, Florida. 20th century. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory.

The seafood industry in Apalachicola is as important today as it was more than 175 years ago. It is the seafood industry that has most significantly shaped the culture and maritime heritage of Apalachicola and it is the seafood industry that anchors a growing nature-based tourism industry throughout the region.

Oysters were Apalachicola’s first seafood industry. Oysters were sold locally as early as 1836, harvested much the same as they are today with scissor-shaped tongs hoisted aboard shallow-draft skiffs. By 1850, oysters had begun to be packed in barrels and shipped aboard steamers headed north or to other neighboring states.

Sustained commercial seafood success began in the late 1880s when German immigrant Herman Ruge, along with his two sons John G. and George H. Ruge opened the Ruge Brothers Canning company in 1885. Through the technique of pastereurization, the Ruge’s became Florida’s first successful commercial seafood packers. John Ruge is also credited as an early advocate of planting oysters shells near existing oyster “beds” to provide places for spat to settle during spawning. Other prominent oyster industry pioneers included Joseph Messina, an early seafood dealer who took over the Bay City Packing Company in 1896 and packed oysters and shrimp under the trademark “Pearl Brand.” By 1915, the Bay City Packing Company shipped canned shrimp to northern markets.

Buildings of the Bay City Packing Co. in Apalachicola, Florida. 1910 (circa). State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory.

There were several large and small seafood dealers in Apalachicola by the 20th century. By 1915, fishing and oystering ranked as Franklin County’s second most important industry behind lumber and Franklin County led the state in oyster production.

Shrimp were plentiful in the bay area but were not commercially successful until around 1900 when haul seines was introduced. Other developments such as the trawl enabled the shrimping industry to thrive and it soon matched the successful oyster industry. Then, as now, seafood industry workers were resourceful. When shrimping or oystering was slack, boat owners often switched to catching blue crab or other commercially lucrative product, including finfish such as mullet or sturgeon.

Although their numbers may have dwindled from the commercial success of the early 1900s, there are still several seafood dealers located along Apalachicola’s historic riverfront. Now, as then, fishermen laden with shrimp, oysters and finfish dock along the riverfront unload bushels of fresh Apalachicola seafood onto the docks much the same way as their ancestors did years ago.

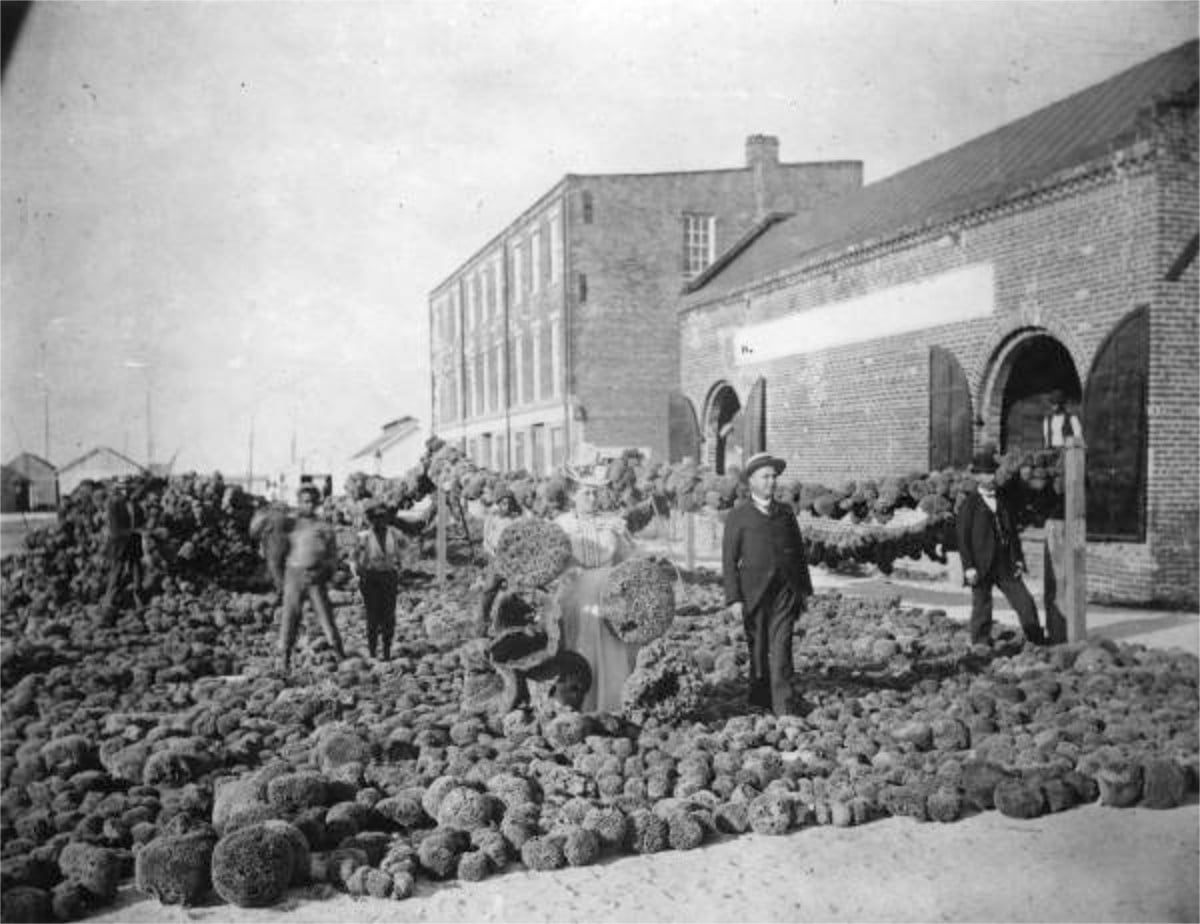

Sponge Industry

From the mid-1870’s to the early decades of the twentieth century, Apalachicola was part of Florida’s sponge industry. The local sponge trade came to rank third in the state. By 1895, over 100 men made their living locally in the short-lived but profitable Apalachicola sponge industry. In 1879, Apalachicola had 16 sponge vessels. The larger vessels would put out to sea for four weeks or more and carried several dinghies or small rowboats. The sponges were taken by “hooking.” The hooker sat in the bow and scanned the water for sponges.

The oarsman than moved the boat into position, and the hooker used a long pole with a sharp-pronged tool on the end to bring up the sponges. Once the larger vessel had a full cargo it returned to port. The three principal buyers of sponges were M. Brash, Sr., John G. Ruge, and Joseph Messina. The buyers inspected the catch and made sealed bids. The sponges were later shipped to San Francisco, St. Louis, Baltimore, and New York.

By 1895, between 80 and 120 men were employed in it, and the city had two sponge warehouses. Later, as the major Greek sponge operations moved down the coast to Carrabelle, Cedar Key and Tarpon Springs, shrimp and sponge operations continued in Apalachicola with the Greek sailing fleet. Today, there are two original sponge warehouses remaining in Apalachicola’s historic downtown district. The Sponge Exchange, built in 1840, is one of the original sponge warehouses.

Apalachicola During the Civil War

When the Civil War began, the Apalachicola River was a vital transportation artery. With its Chattahoochee and Flint River tributaries navigable as far north as Columbus and Albany in Georgia, the river provided access to Apalachicola, a vital Southern shipping port.

Part of the Union strategy for waging the Civil War was to blockade the Southern coastline, choking off commerce and slowly strangling the Confederacy. Rivers like the Apalachicola could then be used to access the interior. As part of the Union naval strategy to blockade Southern ports, the U.S. Navy closed access to the Chattahoochee River system at Apalachicola on June 11, 1861 and maintained its coastal presence there for the remainder of the war.

The Confederates responded by fortifying upstream, placing heavy cannons along their banks in a desperate effort to hold back the gunboats of the Union Navy.

Southern forces defended the town for the first year of the war, but by Spring of 1862 the Confederate forces had evacuated the town, principally due to the fact that the state convention abolished the state militia, who were garrisoning Apalachicola. It took the Union ships blockading the port a week to discover that all the troops were gone. A boat expedition into town could find nobody with the authority to surrunder the City. Unsatisfied, the Union commander launched a larger expedition capturing six sailing vessels and telling the town’s few remaining residents they could continue to fish and oyster as long as they took no action to support the Confederate government. The first capture and occupation of Apalachicola lasted just a few hours.

The Union navy settled into a long, dull presence on the coast, while Confederate officers and engineers upriver struggled to build a ship that could break the blockade and restore trade to the region. The strategic importance of the blockade was threefold: Columbus, Ga., one of the most industrialized cities in the Deep South, sat at the head of the navigable portion of the Chattahoochee River; Apalachicola, a major shipping center, lay on the coast; and a fertile cotton-growing region, the lifeblood of the Southern economy, sprawled between the two.

Apalachicola became a ghost of its antebellum self since the blockade cut off all trade to and from the port. The overall effect of the blockade was to swiftly shift economic and military importance elsewhere for the remainder of the war.

Although Apalachicola suffered economically as a result of the Civil War, the city made transition to peacetime with a brief revival of the cotton trade until railroads, destroyed in Georgia during the war, were rebuilt. Then Apalachicola entered a decade of economic stagnation until the lumber industry began to blossom in the late 1870s and heralded a new economic life for the City.