Black History Trail

Black Businesses on the Hill

Black Businesses on the Hill

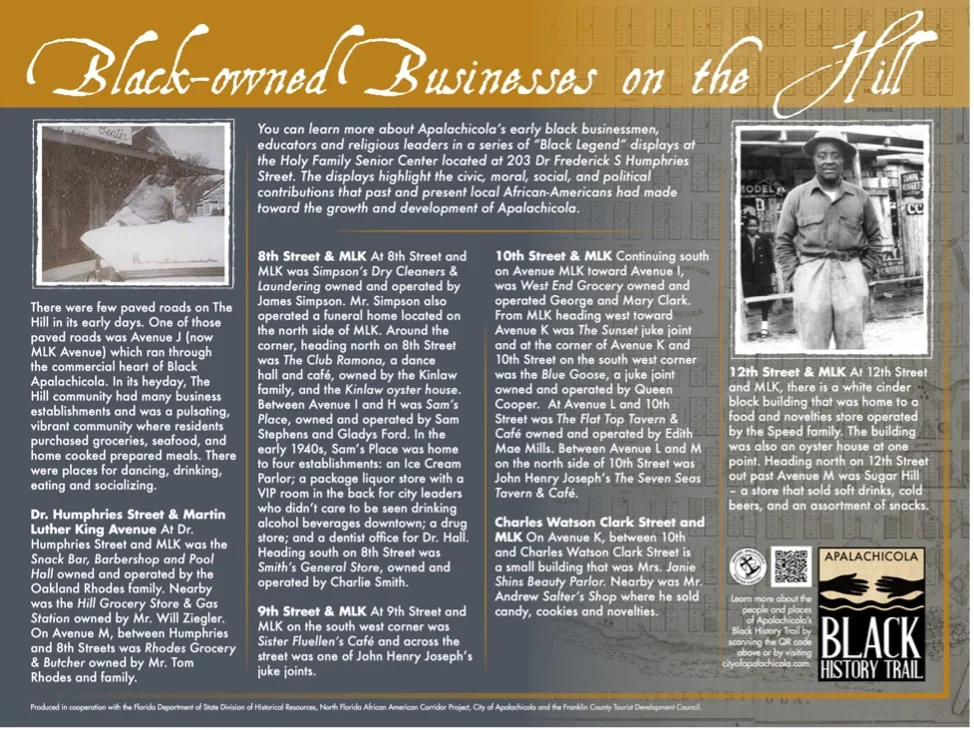

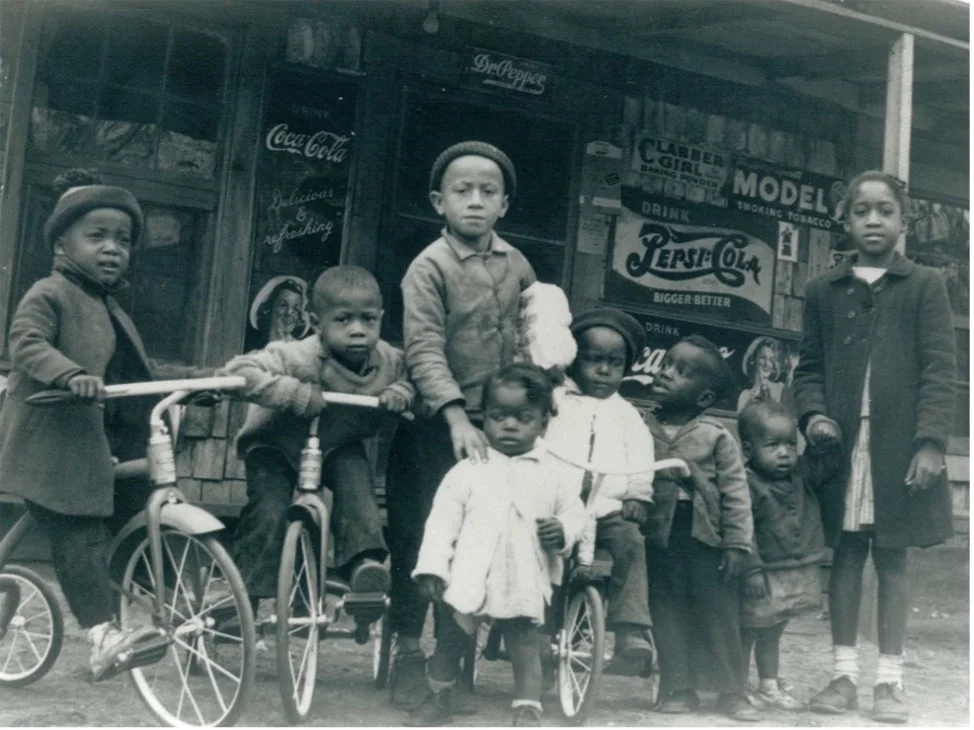

There were only a few paved roads on The Hill in its early days. One of those paved roads was Avenue J (now MLK Avenue) which ran through the commercial heart of Black Apalachicola. In its heyday, The Hill community had many business establishments.

Dr. Humphries Street & Martin Luther King Avenue At Dr. Humphries Street and MLK was the Snack Bar, Barbershop and Pool Hall owned and operated by the Oakland Rhodes family. Traveling south toward Avenue I, was the Hill Grocery Store & Gas Station owned by Mr. Will Ziegler. James Baker was the butcher. Traveling north on Dr. Humphries Street, on Avenue M, between Humphries and 8th Streets was Rhodes Grocery & Butcher owned and operated by Mr. Tom Rhodes and family.

8th Street & MLK At 8th Street and MLK was Simpson’s Dry Cleaners & Laundering owned and operated by James Simpson. Mr. Simpson also operated a funeral home located on the north side of MLK between Dr. Humphries and 8th Streets. Around the corner, heading north on 8th Street toward Avenue K on the east side of the Street was The Club Ramona, a dance hall and café, owned by the Kinlaw family, and the Kinlaw oyster house. On the north side of Avenue K and 8th Street was Chester and Lottie Rhodes’ Funeral Home and Salvage Yard. The Rhodes family also had a laundromat and an ice cream parlor. Heading south on 8th Street, between Avenue I and H, on the north side of the street, was Sam’s Place, owned and operated by Sam Stephens and Gladys Ford. In the early 1940s, Sam’s Place was home to four establishments: an Ice Cream Parlor; a package liquor store with a VIP room in the back for White city and county officials who didn’t care to be seen drinking alcohol beverages downtown; a drug store; and a dentist office for Dr. Hall, an African American from Port St. Joe Florida. Heading south on 8th Street over to 8th and Avenue E was Smith’s General Store, owned and operated by Charlie Smith.

9th Street & MLK At 9th Street and MLK on the southwest corner was Sister Fluellen’s Café and across the street was one of John Henry Joseph’s juke joints.

10th Street & MLK Continuing south on Avenue MLK at 10th Street, heading south toward Avenue I, between 9th and 10th on the north side of the Avenue was West End Grocery owned and operated George and Mary Clark. From MLK heading west toward Avenue K was The Sunset juke joint and at the corner of Avenue K and 10th Street on the southwest corner was the Blue Goose, a juke joint owned and operated by Queen Cooper. At Avenue L and 10th Street on the northeast corner was The Flat Top Tavern & Café owned and operated by Edith Mae Mills. Between Avenue L and M on the north side of 10th Street was John Henry Joseph’s The Seven Seas Tavern & Café.

10th Street & MLK Continuing south on Avenue MLK at 10th Street, heading south toward Avenue I, between 9th and 10th on the north side of the Avenue was West End Grocery owned and operated George and Mary Clark. From MLK heading west toward Avenue K was The Sunset juke joint and at the corner of Avenue K and 10th Street on the southwest corner was the Blue Goose, a juke joint owned and operated by Queen Cooper. At Avenue L and 10th Street on the northeast corner was The Flat Top Tavern & Café owned and operated by Edith Mae Mills. Between Avenue L and M on the north side of 10th Street was John Henry Joseph’s The Seven Seas Tavern & Café.

Charles Watson Clark Street and MLK At Charles Watson Clark Street and MLK, head north to Avenue K. On Avenue K, between 10th and Charles Watson Clark Street on the south side of the Avenue, at the alley is a small building - this was Mrs. Janie Shins Beauty Parlor. Continue on Charles Watson Street to Avenue M, between M and the Public Housing complex, on the east side of the street was Mr. Andrew Salter’s Shop where he sold candy, cookies and novelties.

12th Street & MLK At 12th Street and MLK, head north on 12th Street and on the west side of the Street is a white cinder block building that was home to a food and novelties store operated by the Speed family. The building was also an oyster house at one point. The May’s family had a lumber saw on the south side of 12th Street where wood was cut and sold to residents for their woodburning stoves. Heading north on 12th Street out past Avenue M on the west side of the street across from the Public Housing complex was Sugar Hill – a store that sold soft drinks, cold beers, and an assortment of snacks.

Cafés & Recreational Establishments: Fry’s Café and Pool Hall, Green Lantern Tavern & Dancing, Royal Café , The Oaks Café , Sugar Hill Store

The Hill was a pulsating, vibrant community with multiple commercial establishments where community residents purchased groceries, seafood, and home cooked prepared meals. There were places for dancing, drinking, eating, visiting, and ostentatious joy making.

Today, The Hill is home to people from across the United States and the new residents are not all African American. The community needs gathering spaces, designed to welcome long time Hill residents and new residents into conversations that create a solid community of 21st Century residents on The Hill.

Minnie Barefield’s Mansion

Minnie Barefield’s Mansion

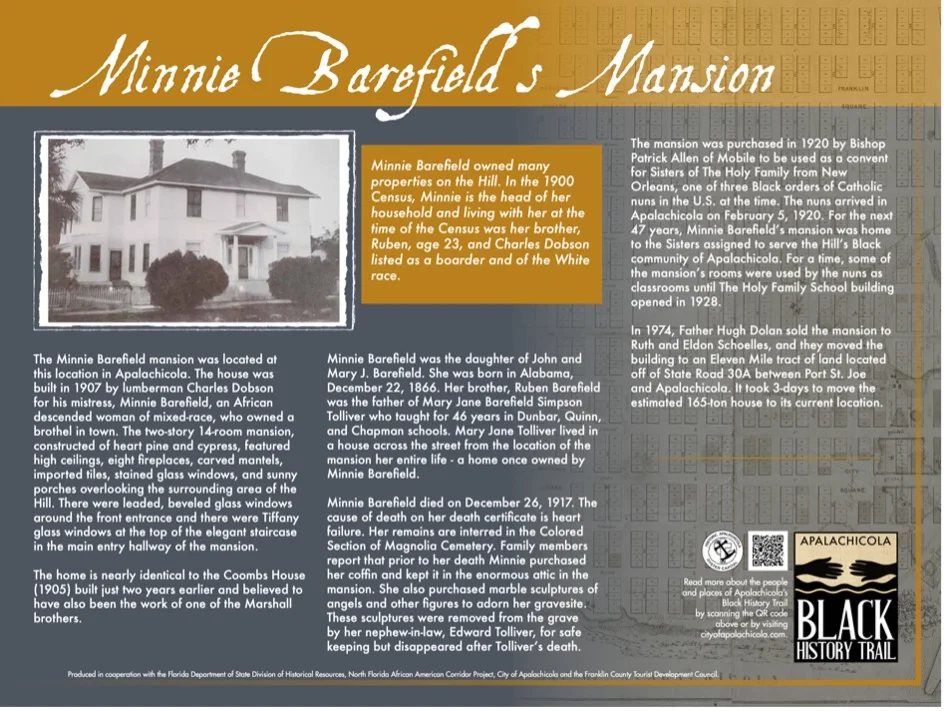

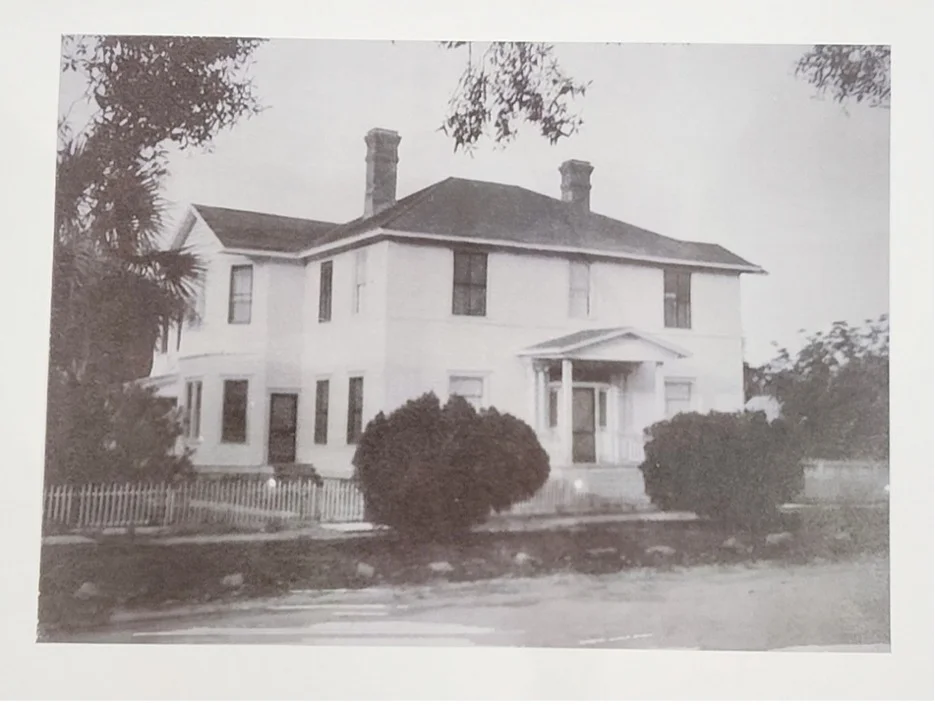

The Minnie Barefield mansion was located adjacent to the Holy Family School on 7th Street. The house was built in 1907 by lumberman Charles Dobson for his mistress, Minnie Barefield, an African descended woman of mixed-race, who owned a brothel in town. The two-story 14-room mansion, constructed of heart pine and cypress, featured high ceilings, eight fireplaces, carved mantels, imported tiles, stained glass windows, and sunny porches overlooking the surrounding area of the Hill. There were leaded, beveled glass windows around the front entrance and there were Tiffany glass windows at the top of the elegant staircase in the main entry hallway of the mansion. The home is nearly identical to the Coombs House (1905) built just two years earlier and believed to have also been the work of one of the Marshall brothers.

Minnie Barefield was the daughter of John and Mary J. Barefield. She was born in Alabama, December 22, 1866. Her brother, Ruben Barefield was the father of Mary Jane Barefield Simpson Tolliver who taught for 46 years in Dunbar, Quinn, and Chapman schools. Mary Jane Tolliver lived in a house across the street from the location of the mansion her entire life. The home Mary Jane and her family lived in was once owned by Minnie Barefield.

Minnie Barefield owned many properties on the Hill. In the 1900 Census, Minnie is the head of her household and living with her at the time of the Census was her brother, Ruben, age 23, and Charles Dobson listed as a boarder and of the White race.

Minnie Barefield died on December 26, 1917. The cause of death on her death certificate is heart failure. Her remains are interred in the Colored Section of Magnolia Cemetery. Family members report that prior to her death Minnie purchased her coffin and kept it in the enormous attic in the mansion. She also purchased marble sculptures of angels and other figures to adorn her gravesite. These sculptures were removed from the grave by her nephew-in-law, Edward Tolliver, for safe keeping. Unfortunately, the ornamental figurines disappeared after Edward Tolliver’s death in 2001.

Minnie Barefield died on December 26, 1917. The cause of death on her death certificate is heart failure. Her remains are interred in the Colored Section of Magnolia Cemetery. Family members report that prior to her death Minnie purchased her coffin and kept it in the enormous attic in the mansion. She also purchased marble sculptures of angels and other figures to adorn her gravesite. These sculptures were removed from the grave by her nephew-in-law, Edward Tolliver, for safe keeping. Unfortunately, the ornamental figurines disappeared after Edward Tolliver’s death in 2001.

The mansion was purchased in 1920 by Bishop Patrick Allen of Mobile to be used as a convent for Sisters of The Holy Family from New Orleans, one of three Black orders of Catholic nuns in the U.S. at the time. The nuns arrived in Apalachicola on February 5, 1920. For the next 47 years, Minnie Barefield’s mansion was home to the Sisters assigned to serve the Hill’s Black community of Apalachicola. For a time, some of the mansion’s rooms were used by the nuns as classrooms until The Holy Family School building opened in 1929.

In 1974, Father Hugh Dolan sold the mansion to Ruth and Eldon Schoelles, and they moved the building to an Eleven Mile tract of land located off of State Road 30A between Port St. Joe and Apalachicola. It took 3-days to move the estimated 165-ton house to its current location.

Odd Fellows Hall

Odd Fellows Hall

The Odd Fellows Hall at 143 Sixth Street was built between 1881 and 1883 as a meeting hall for the local black fraternal order. The period from the end of the Civil War to the First World War has been called the golden age of social fraternities. Industrialization brought people together off the farms and gave them more time for leisure activities. Before radio and television fraternal orders provided an avenue for socialization and a sense of community. Freemasons, Odd Fellows and Knights of Pythias all had local black chapters.

The two-story wooden structure originally had a two-story porch just across the southwestern façade facing Sixth Street. The distinctive clipped gables are known as a jerkin head roof.

The downstairs space was rented out to businesses. At one point a skating rink was in the building. The second floor housed the meeting room for the lodge. Besides lodge meetings the space was also used by other organizations and community groups as a meeting space. In 1890 the Odd Fellows Hall hosted a meeting of the black sawmill workers when they decided to go on strike for higher wages. During the construction of the John Gorrie Bridge in the 1930 the hall hosted regular dances.

Eventually the local Odd Fellows disbanded, and the building fell into disuse. After sitting vacant for several years, it was purchased by the City of Apalachicola in 1987 and the structure was renovated into several apartments. The porches stretching down each side of the building were added at this time. The city sold the property in 1998. It is in private ownership today.

Eventually the local Odd Fellows disbanded, and the building fell into disuse. After sitting vacant for several years, it was purchased by the City of Apalachicola in 1987 and the structure was renovated into several apartments. The porches stretching down each side of the building were added at this time. The city sold the property in 1998. It is in private ownership today.

Wallace M. Quinn High School

Wallace M. Quinn High School, grades 1 to 12, was the premier educational institution for Franklin County’s Black communities during the years of federal policy that permitted state governments to enforce the separation of Black children into underfunded public schools. Notwithstanding the political intent of the federal policy and state actions, this particular underfunded school for Black people was transformed into a center of excellence by the Black residents and teachers of Franklin County.

The story of providing educational opportunities to Black people in Apalachicola begins immediately after Emancipation spearheaded by Emanuel Smith, formerly enslaved, who was instrumental in organizing church schools, and “The Colored School of Apalachicola”. When Dunbar was destroyed by fire on February 11, 1943, a new school for Black children was needed.

The possibility of a new school became a reality when Wallace M. Quinn, a Euro-American Maryland businessman who built Menhaden/pogie plants to process oil from fish, purchased and donated to the county 21 acres of land at this site for the construction of a school for Black children. Quinn made this gift to strengthen efforts on behalf of his business to recruit potential Black employees to Apalachicola.

The possibility of a new school became a reality when Wallace M. Quinn, a Euro-American Maryland businessman who built Menhaden/pogie plants to process oil from fish, purchased and donated to the county 21 acres of land at this site for the construction of a school for Black children. Quinn made this gift to strengthen efforts on behalf of his business to recruit potential Black employees to Apalachicola.

Construction of Quinn High School was completed in April 1945. An Industrial Arts Building was added to the campus in the area where the water park for children now stands, and in 1959, a gymnasium was added complete with locker rooms, storage rooms, and public restrooms. Prior to the construction of the gymnasium, Quinn’s girls’ and boys’ basketball teams competed on an outside court made of asphalt. Lights from cars and trucks parked around the court illuminated the basketball court for night games. On cold nights, heat was provided by fires in burn barrels placed strategically around the asphalt court. Travel to and from away games along the highways of North Florida was often fraught with anxiety, and coaches cautioned students to be quiet as they passed through towns noted for racial bigotry.

A Dedication of Gymnasium ceremony was held on Sunday, September 20, 1959, at 4:00 pm for the new gymnasium. The dedicatory address was delivered by Alonzo “Jake” Gaither, legendary football coach and head of the Physical Education Department at Florida Agricultural & Mechanical University.

The grandeur of the ceremony for the dedication of the gymnasium is an indicator of the serious attention brought to every detail of the educational experience at Quinn. In early 1950s, when Charles Watson-Clark was hired to teach mathematics and science at Quinn High, the local school board passed a rule that no Black student at Quinn was to be taught algebra 1 & 2, geometry, chemistry, or physics. Only general mathematics and biology were to be taught. Mr. Watson-Clark noted that he knew that this rule was meant to prevent Black students from being competitive. Charles Watson-Clark, with the agreement of Principal Willie L. Speed, prepared two curricula – one was used whenever he was observed by people from the all-white local school board, and the other he taught in classes that were unobserved. He also taught students at his home on the weekends. His activism and commitment to excellence ensured that graduates of Quinn High School were prepared to pursue degrees in mathematics, and all of the sciences.

When Quinn High administration and faculty requested that Black students be provided instruction in the use of typewriters, the school board gave permission to hire a teacher for the course. However, the board approved the purchase of one typewriter.

Graduates of Wallace M. Quinn High School excelled. A 1953 graduate, Dr. Frederick S. Humphries became the president of two HBCUs, Tennessee A&I University (Nashville TN) and Florida A&M University (Tallahassee FL). Graduates distinguished themselves as college administrators and professors, superintendents of schools, school district administrators, and schoolteachers. One graduate became a postmaster in midtown Manhattan. Others were jurists, physicians, a director of pharmacy at Hubbard/Meharry Medical College, builders, clergy, and many other career paths including all branches of the US military.

Graduates of Wallace M. Quinn High School excelled. A 1953 graduate, Dr. Frederick S. Humphries became the president of two HBCUs, Tennessee A&I University (Nashville TN) and Florida A&M University (Tallahassee FL). Graduates distinguished themselves as college administrators and professors, superintendents of schools, school district administrators, and schoolteachers. One graduate became a postmaster in midtown Manhattan. Others were jurists, physicians, a director of pharmacy at Hubbard/Meharry Medical College, builders, clergy, and many other career paths including all branches of the US military.

In the twenty-two years of its existence, Quinn High was a community school and the center of the African American communities in Franklin County. Students (ages 6 to 18) were bused daily, 48 miles roundtrip, to the school from Carrabelle FL. Black teachers taught generations of children from the same families and for 14 years of its existence, Quinn High had the same principal, Willie L. Speed. Wallace M. Quinn High School was closed in 1967 when schools in Franklin County finally integrated. What follows is a partial list of educators who taught at Wallace M. Quinn High School: Mrs. Idell Baker, Mrs. Retha M. McCaskill, Mrs. Mary B. Tolliver, Mrs. Ruby Tampa, Mrs. Louise C. Baker, Mrs. Margaret T. May, Mr. Charles Watson-Clark, Mr. Willie Speed, Mrs. Lois B. Baker, Mr. James Gautier, Mrs. Eva Z. W. Tolliver, Mrs. Wilhelmina Spires, Mr. Chester Rhodes, Jr., Mr. Jared Bruns. Quinn High School principals were Mr. W. Campbell (1946-1951), Mr. S. J. Cooper (1951-1954), and Mr. W. L. Speed (1954-1968).

This commemorative marker brings into the public square redemptive stories of the sheer will and determination of African American people from all walks of life to acquire an education. These stalwarts were undeterred by the policies of dehumanization enacted by their governments. They created a community school that affirmed and validated their humanity and ensured that they and their progeny had a future filled with respect for self, and love for the humanity and dignity of all people.

Holy Family School and Church

Holy Family School and Church

In 1917, Mercy Paige, a Black resident of Apalachicola, wrote a letter to Bishop Patrick Allen in Mobile Alabama requesting that he establish a mission in Apalachicola for Black people because “the field of souls in the area was ripe for the harvest.”

In 1920, according to Deed Book U, Page 362, on January 10, S. E. Teague and Mabel Teague, his wife, of Franklin County, Florida, sold to Edward P. Allen, Bishop of Mobile and his successors in office, of Mobile, Alabama, Lots 8, 9, & 10, Block 176, City of Apalachicola, for $2,000. This would have been Minnie Barefield’s house. Furthermore, Deed Book U, Page 423, shows that on February 1, 1920, Seaborn Barefield and Georgia Barefield, his wife, of Franklin County, Florida, sold to Edward P. Allen, Bishop of Mobile and his successors in office, of Mobile, Alabama, Lots 2, 3, 6, 7 and 11’ of Lot 1, Block 176, City of Apalachicola, for $2,700. At the time, on the property, there were several small houses and Minnie Barefield’s fourteen-room mansion. A small house was renovated and used for a chapel, and one of the small houses was used for a rectory. Francis de Sales, a Franciscan Missioner, on sick leave living in the Diocese of Mobile, was appointed pastor at Holy Family.

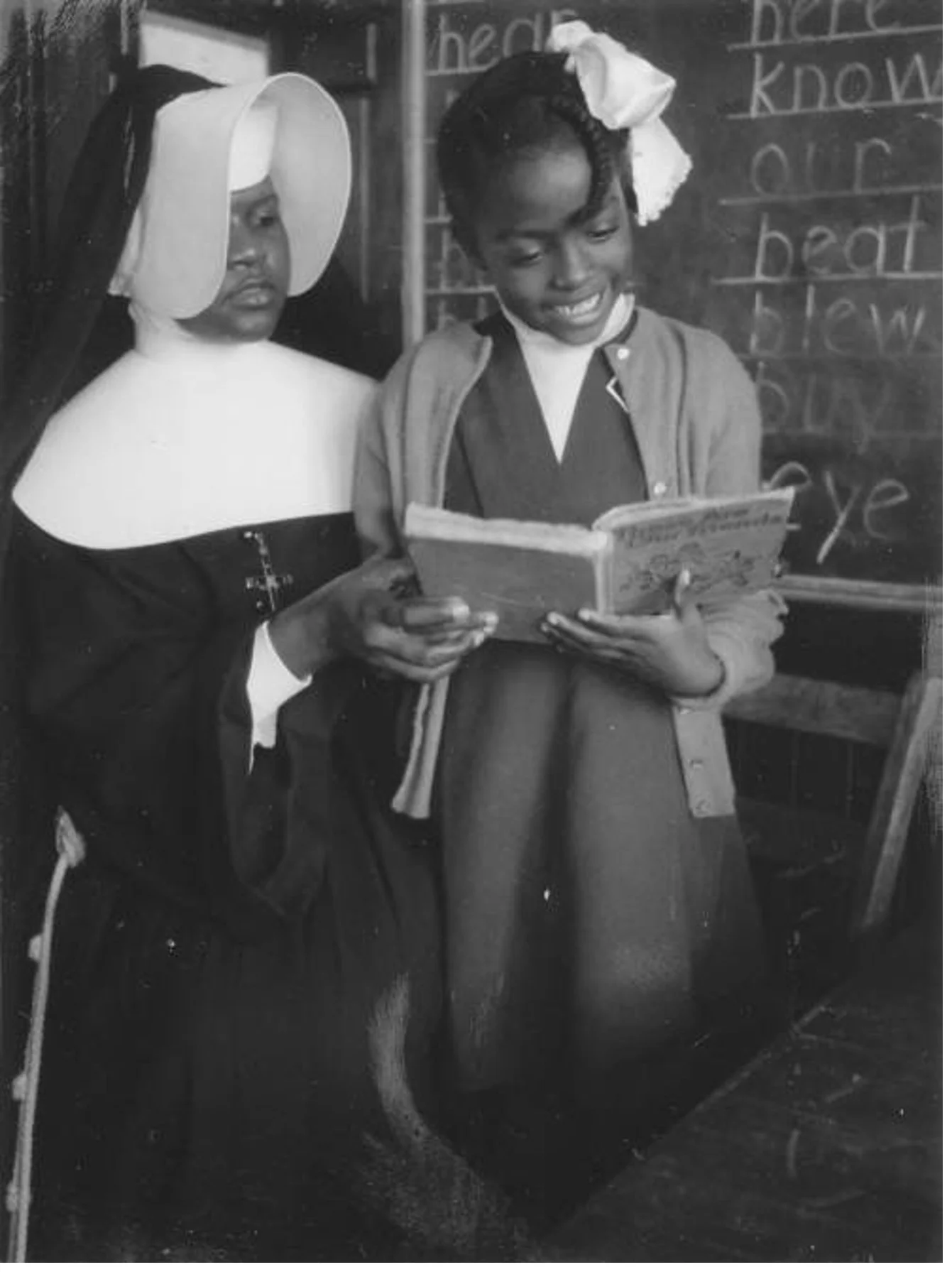

On February 5, 1920, a group of nuns from the missionary Congregation of the Sisters of the Holy Family (one of three orders of African American nuns in the U.S.) arrived from New Orleans to serve the new mission in Apalachicola. Twenty years before the Civil War of the United States, and before it was legal for such a Congregation to exist, the Sisters of the Holy Family were founded in New Orleans, Louisiana by Henriette DeLille, a free woman of color. Co-foundresses of this religious community of African-American women were Juliette Gaudin and Josephine Charles.

In 1922, the Sisters were commissioned to open a school, and seventy-seven students enrolled. The majority of the students were non-Catholic. In 1925, there were eighty-five students enrolled in the school. Reverend Thomas H. Massey became pastor at Holy Family in 1926. The increasing enrollments of students supported the need for a school dedicated to this work. The Sisters and Father Massey made it possible for a school to be built. Bishop Toolen dedicated the new school building on August 28, 1928.

The building housed four large classrooms, and an auditorium which was used as a parish church. In 1943 when Holy Family Mission celebrated its Silver Jubilee, there were 125 pupils enrolled in the school with four teachers. There were two grades in each of the four classrooms.

Sister Mary Barbara served the children and residents of The Hill for 32 years and she was the Superior for the nuns during most of her time in Apalachicola. She was deeply loved and respected. Sister Mary Barbara left the Holy Family Mission in 1951.

Father Massey served the people of Apalachicola for 25 years. During his time at Holy Family, he baptized 212 people. When he left in 1951, the parish was served by the Congregation of the Resurrection Fathers with Rev. Stephen Juda replacing Fr. Massey as pastor. On January 2, 1959, the Society of St. Edmund was assigned to serve Holy Family Mission. Rev. Edward Stapleton was pastor for a short time when he was replaced by Father Lawrence Boucher, who remained at the parish until 1968.

Father Massey served the people of Apalachicola for 25 years. During his time at Holy Family, he baptized 212 people. When he left in 1951, the parish was served by the Congregation of the Resurrection Fathers with Rev. Stephen Juda replacing Fr. Massey as pastor. On January 2, 1959, the Society of St. Edmund was assigned to serve Holy Family Mission. Rev. Edward Stapleton was pastor for a short time when he was replaced by Father Lawrence Boucher, who remained at the parish until 1968.

The Sisters of the Holy Family served the people of Apalachicola from 1920 until the closing of the mission in 1968. Hundreds of children were taught by the Sisters and the corridors of the building contain many black & white photos of the children, the nuns, and the spaces they used for prayer, teaching/learning, and recreation.

In June 1968, the Sisters of the Holy Family withdrew from the Apalachicola Parish, as did the Edmundite Fathers, and the school closed. On July 1, 1968, Northwest Florida was transferred from the Diocese of Mobile-Birmingham to the Diocese of St. Augustine. Rev. John C. Carroll Bender was then pastor at the Holy Family Church and, St. Patrick, the Catholic Church for White people.

Black parishioners continued to attend mass at the Holy Family Catholic Church which persisted until 1987. In spite of great financial odds, the Church was self-sustaining until its last days.

In 1974 Father Hugh E. Dolan sold the Holy Family convent to Eldon and Ruth Schoelles for $16,000. The convent was moved to a site on the bay between Apalachicola and Port St. Joe.

In 2004, the City of Apalachicola obtained the building from the Diocese. With a variety of funds, the building was renovated to serve the people of Apalachicola as a Senior Citizen Center. The revitalized building opened in 2012.

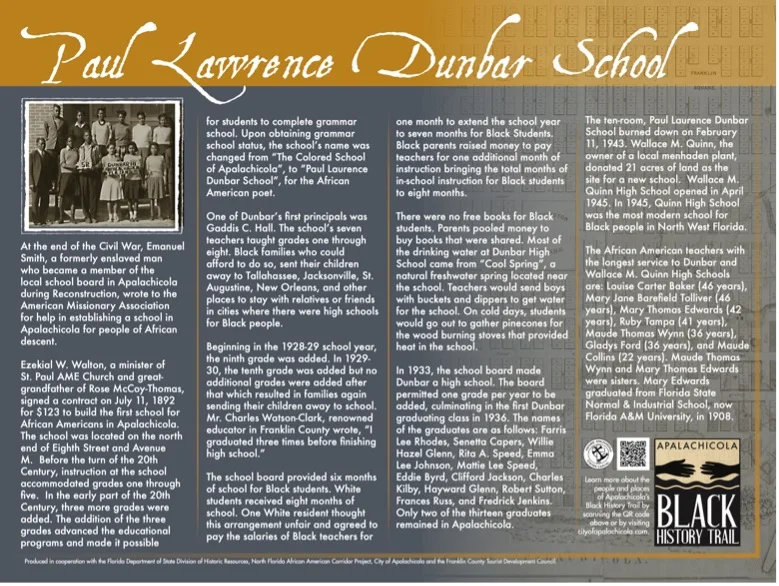

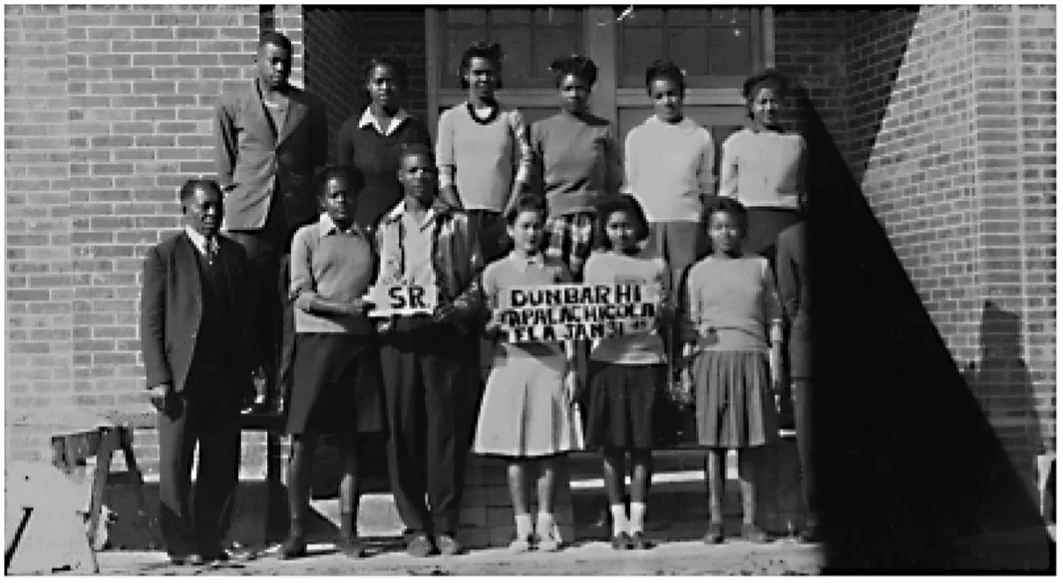

Paul Laurence Dunbar School

Paul Laurence Dunbar School

At the end of the Civil War, Emanuel Smith, a formerly enslaved man who became a member of the local school board in Apalachicola during Reconstruction, wrote to the American Missionary Association for help in establishing a school in Apalachicola for people of African descent.

Ezekial W. Walton, a minister of St. Paul AME Church and great-grandfather of Rose McCoy-Thomas, signed a contract on July 11, 1892 for $123 to build the first school for African Americans in Apalachicola. The school was located on the north end of Eighth Street and Avenue M. Before the turn of the 20th Century, instruction at the school accommodated grades one through five. In the early part of the 20th Century, three more grades were added. The addition of the three grades advanced the educational programs and made it possible for students to complete grammar school. Upon obtaining grammar school status, the school’s name was changed from “The Colored School of Apalachicola”, to “Paul Laurence Dunbar School”, for the African American poet.

One of Dunbar’s first principals was Gaddis C. Hall. The school’s seven teachers taught grades one through eight. Black families who could afford to do so, sent their children away to Tallahassee, Jacksonville, St. Augustine, New Orleans, and other places to stay with relatives or friends in cities where there were high schools for Black people.

Beginning in the 1928-29 school year, the ninth grade was added. In 1929-30, the tenth grade was added. At that point no additional grades were added which resulted in families again having to make great sacrifices to send their children away to school. Mr. Charles Watson-Clark, renowned educator in Franklin County wrote, “I graduated three times before finishing high school.”

The school board provided six months of school for Black students. White students received eight months of school. One White resident thought this arrangement unfair and agreed to pay the salaries of Black teachers for one month to extend the school year to seven months for Black Students. Black parents raised money to pay teachers for one additional month of instruction bringing the total months of in-school instruction for Black students to eight months.

There were no free books for Black students. Parents pooled money to buy books that were shared. Most of the drinking water at Dunbar High School came from “Cool Spring”, a natural freshwater spring located near the school. Teachers would send boys with buckets and dippers to get water for the school. On cold days, students would go out to gather pinecones for the wood burning stoves that provided heat in the school.

There were no free books for Black students. Parents pooled money to buy books that were shared. Most of the drinking water at Dunbar High School came from “Cool Spring”, a natural freshwater spring located near the school. Teachers would send boys with buckets and dippers to get water for the school. On cold days, students would go out to gather pinecones for the wood burning stoves that provided heat in the school.

In 1933, the school board made Dunbar a high school. The board permitted one grade per year to be added, culminating in the first Dunbar graduating class in 1936. The names of the graduates are as follows: Farris Lee Rhodes, Senetta Capers, Willie Hazel Glenn, Rita A. Speed, Emma Lee Johnson, Mattie Lee Speed, Eddie Byrd, Clifford Jackson, Charles Kilby, Hayward Glenn, Robert Sutton, Frances Russ, and Fredrick Jenkins. Only two of the thirteen graduates remained in Apalachicola. The other graduates joined the Great Migration out of Apalachicola in search of brighter futures.

The ten-room, Paul Laurence Dunbar School burned down on February 11, 1943. Classes were held in the Masonic and Odd Fellows Halls on 6th Street. Wallace M. Quinn, the owner of a local menhaden (pogie) plant, donated twenty-one acres of land as the site for a new school for Black people. Wallace M. Quinn High School opened in April 1945. In 1945, Quinn High School was the most modern school for Black people in North West Florida.

The African American teachers with the longest service to Dunbar and Wallace M. Quinn High Schools are: Louise Carter Baker (46 years), Mary Jane Barefield Tolliver (46 years), Mary Thomas Edwards (42 years), Ruby Tampa (41 years), Maude Thomas Wynn (36 years), Gladys Ford ( (36 years), and Maude Collins (22 years). Maude Thomas Wynn and Mary Thomas Edwards were sisters. Mary Edwards graduated from Florida State Normal & Industrial School, now Florida A&M University, in 1908.

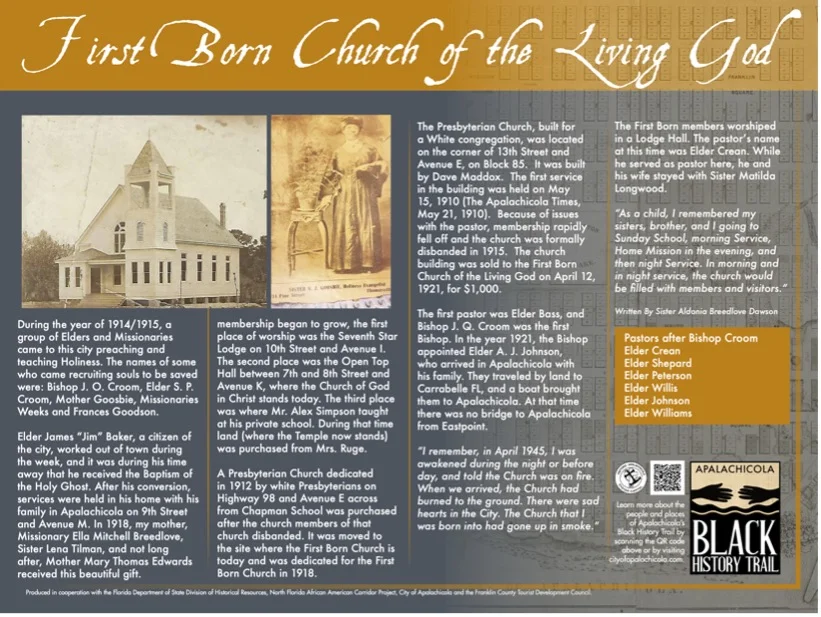

First Born Church of the Living God

First Born Church of the Living God

During the year of 1914/1915, a group of Elders and Missionaries came to this city preaching and teaching Holiness. Quite a few people received the gift of the Holy Ghost along with speaking in other tongues. The names of some who came recruiting souls to be saved were: Bishop J. Q. Croom, Elder S. P. Croom, Mother Goosbie, Missionary Weeks, Missionary Frances Goodson, and a few more from the early church.

Elder James “Jim” Baker, a citizen of the city, worked out of town during the week, and it was during his time away that he received the Baptism of the Holy Ghost. After his conversion, services were held in his home with his family in Apalachicola on 9th Street and Avenue M. His wife and most of his children were saved during that time, as were, Missionary Mamye Hines (mother of Mrs. Catharine Walton) Sister Arstene Young Posser, Sister Mozell Allen Staley, Sister Carrie Tilman, and Sister Mamie Davis (Sister Freddie May Bailey’s mother).

In 1918, my mother, Missionary Ella Mitchell Breedlove, Sister Lena Tilman, and not long after, Mother Mary Thomas Edwards received this beautiful gift.

As membership began to grow, the first place of worship was the Seventh Star Lodge on 10th Street and Avenue I. The second place was the Open Top Hall between 7th and 8th Street and Avenue K, where the Church of God in Christ stands today. The third place was where Mr. Alex Simpson taught at his private school. During that time land (where the Temple now stands) was purchased from a white lady, Mrs. Ruge.

A Presbyterian Church, built by Dave Maddox, that was dedicated in 1912 by white Presbyterians on Highway 98 (Avenue E and 13th Street) across from Chapman School was purchased for $1,000, after the white church members of that church disbanded. It was moved to the site where the First Born Church is today and was dedicated for the First Born Church in 1921. I feel like we were in the Apalachicola District because of the membership and the beautiful Temple with high ceilings, oak flooring, knotted pine walls, the beautiful pulpit, and altar with swinging vestibule doors. As children we were proud to say, let us go to the House of The Lord.

The first pastor was Elder Bass, and Bishop J. Q. Croom was the first Bishop. In the year 1921, the Bishop appointed Elder A. J. Johnson, who arrived in Apalachicola with his family. They traveled by land to Carrabelle FL, and a boat brought them to Apalachicola. At that time there was no bridge to Apalachicola from Eastpoint.

Deacon Shorty Williams of Carrabelle, along with Sister Ella Breedlove, Sister Della Ray, and Sister Austine Pooser Burns met the family at the dock in Apalachicola and brought them to the parsonage. Elder Jackson was Presiding Elder at that time. The Church paid off its mortgage under the pastorate of Elder A. J. Johnson. Sister Eula C. Johnson Sutton said she had never seen another building like the First Born Church of Apalachicola.

Pastors who served at First Born were: Elder Brown from Indian Pass FL (Mother Langston’s father), and Elder G. G. Green. We had a Presiding Elder named McMillian. Elder Croom was a Presiding Elder. In 1932, the year that President Roosevelt was elected, Presiding Elder, A. J. Johnson passed away. It was a sad day to lose a friend during the great depression, but God didn’t leave us alone, He brought us out victorious.

Elder W. B. Bennett was a great Evangelist during the 1930s who ran revivals in Apalachicola. I received the Gift of the Holy Ghost June 1936. Many others received the Gift: Deacon Shins, Deaconess Shins, Deacon Davis, Deacon Wynn, and Brother David Miller among others. Elder G. G. Green of Panama City pastored the Church for 12 years. Then a misunderstanding came about in the First Born Church. Bishop Croom left the Church and some of the members followed.

Elder W. B. Bennett was a great Evangelist during the 1930s who ran revivals in Apalachicola. I received the Gift of the Holy Ghost June 1936. Many others received the Gift: Deacon Shins, Deaconess Shins, Deacon Davis, Deacon Wynn, and Brother David Miller among others. Elder G. G. Green of Panama City pastored the Church for 12 years. Then a misunderstanding came about in the First Born Church. Bishop Croom left the Church and some of the members followed.

I remember, in April 1945, I was awakened during the night or before day, and told the Church was on fire. When we arrived, the Church had burned to the ground. There were sad hearts in the City. The Church that I was born into had gone up in smoke.

The First Born members worshiped in a Lodge Hall. The pastor’s name at this time was Elder Crean. While he served as pastor here, he and his wife stayed with Sister Matilda Longwood.

As a child, I remembered my sisters, brother, and I going to Sunday School, Morning Service, Home Mission in the evening, and then night Service. In morning and in night service, the church would be filled with members and visitors.

Elder Shepard was the next Pastor. He started to build a block building. After the building was a few feet high, something went wrong. In the meantime, Deacon Richard Davis and Brother Faison of Wewahitchka (Deaconess Charissa Bass Williams’ uncle) laid the blocks for this church we now worship in. (Only a shell of this building stands on the site today.)

We will never forget Deacon McKinley Shins, the husband of Deaconess Janie L. Shins. He was a faithful deacon and a good leader of the church. I was told he was the first person that had a vision to celebrate the pastor’s anniversary.

I shall end this history of the church with the names of the pastors of the First Born Church, mostly in the early 1940s. When reading the names let us all remember to serve and obey the Words of the Lord, because tomorrow isn’t promised to us.

Pastors after Bishop Croom: Elder Crean, Elder Shepard, Elder Peterson, Elder Willis, Elder Johnson, Elder Williams

Written By: Sister Aldonia Breedlove Dawson with thanks to Missionary Nancy Davis, Sister Eula C. Johnson Sutton, Sister Maude Thomas Green, and Sister Helen Howe for their assistance in the research.

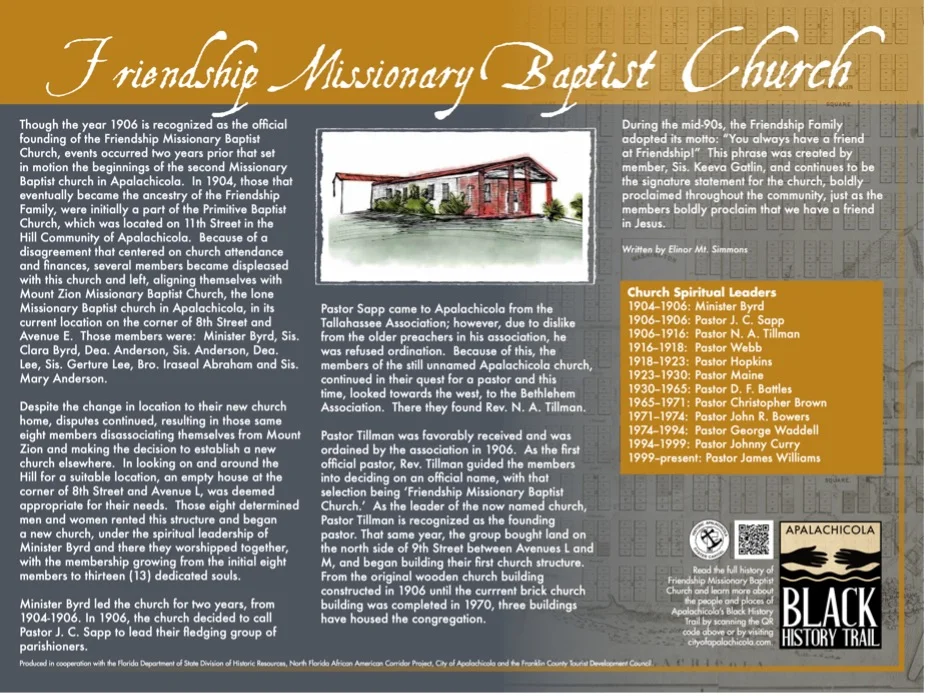

Friendship Missionary Baptist Church

Friendship Missionary Baptist Church

Though the year 1906 is recognized as the official founding of the Friendship Missionary Baptist Church, events, which started two years prior, set in motion the beginnings of the second Missionary Baptist church in Apalachicola. In 1904, those that eventually became the ancestry of the Friendship Family, were initially a part of the Primitive Baptist Church, which was located on 11th Street in the Hill Community of Apalachicola. Because of a disagreement that centered on church attendance and finances, several members became displeased with this church and left, aligning themselves with Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church, the lone Missionary Baptist church in Apalachicola, in its current location on the corner of 8th Street and Avenue E. Those members were: Minister Byrd, Sis. Clara Byrd, Dea. Anderson, Sis. Anderson, Dea. Lee, Sis. Gerture Lee, Bro. Iraseal Abraham and Sis. Mary Anderson.

Despite the change in location to their new church home, disputes continued, resulting in those same eight members disassociating themselves from Mount Zion and making the decision to establish a new church elsewhere. In looking on and around the Hill for a suitable location, an empty house at the corner of 8th Street and Avenue L, was deemed appropriate for their needs. Those eight determined men and women rented this structure and began a new church, under the spiritual leadership of Minister Byrd and there they worshipped together, with the membership growing from the initial eight members to thirteen (13) dedicated souls.

Minister Byrd led this band of Christians for two years, from 1904-1906, providing spiritual guidance; however, the group decided since they were firmly established as a new church, it was time to call an official pastor to continue on as their spiritual leader. Thus, in 1906, they decided to call Pastor J. C. Sapp to lead their fledging group of parishioners. Pastor Sapp came to Apalachicola from the Tallahassee Association; however, due to dislike from the older preachers in his association, he was refused ordination. Because of this, the members of the still unnamed Apalachicola church, continued in their quest for a pastor and this time, looked towards the west, to the Bethlehem Association (which later became the New Gulf Coast Missionary Baptist Association.) There they found Rev. N. A. Tillman.

Pastor Tillman was favorably received by all--the parishioners here in Apalachicola and the association’s leaders--and was ordained by the association in 1906. As the first official pastor, Rev. Tillman guided the members into deciding on an official name, with that selection being ‘Friendship Missionary Baptist Church.’ As the leader of the now named church, Pastor Tillman is recognized as the founding pastor and with the year being 1906, that year is observed as the official founding year of the Friendship Missionary Baptist Church.

The year 1906 continued to be a year of tremendous change for this group. Not only did they finally get an official pastor and finally decide on an official name, they also recognized the need to have an official residence. Therefore, during this year, the members began working towards this goal. Initially, they purchased a lot from Bert Hills, and later on in the same year, purchased additional land adjacent to the previously-purchased lot. With these two parcels of land on the north side of 9th Street between Avenues L and M, they began the process of building their first church structure and fulfilling the goal of having an official residence.

Before the year ended, the hard-working laborers had laid the flooring for their new sanctuary and as they were preparing to build the sides of the structure, Minister Byrd, their first spiritual leader, died. His funeral was the first to be held at the building site, on the newly-finished floor, with those attending the Homegoing service sitting on chairs and stools brought from home.

Building the church took six years, with the completion occurring in 1911. During that time, the membership grew and there were two pastoral changes, each continuing to lead the Friendship Family with their spiritual guidance.

In 1932, as the result of a fire, two/thirds of the church building was destroyed, with the remaining sections being severely damaged, causing the structure to become weak and develop a serious lean. Upon assessing the situation before them, members were faced with difficult decisions, and determined that with repairs to the still standing, but leaning structure, they could safely secure it so that worship service could still be held on site. Salvaging whatever materials that were still usable, the men of the church, along with assistance from men in the community, were able to prop up the leaning portions of the building with wooden beams and make the sanctuary safe for the congregation’s continued, but temporary use. The very next year, in 1933, the members began working on a permanent structure at the same site and this rebuilding project continued for approximately ten (10) years, with the members working diligently to re-create their house of worship.

Under the pastorate of Rev. Christopher Brown in 1965, the members began discussing the building of a brick structure as their church home. For a couple of years, Pastor Brown, who was from Panama City, deliberated with the congregation on this matter, sometimes being embroiled in very intense discussions. Finally, in 1967, he was granted permission to begin building a new brick structure. The wooden church, that had been their second house of worship, had been severely damaged by fire, yet temporarily and eventually permanently rebuilt, was completely torn down, making way for a new and larger brick building.

During this time of demolishing and building, the congregation continued to fellowship and worship with services being held at the church’s parsonage, located at the end of 11th Street in the Hill community. Under the direction of Pastor Brown, a builder himself, the members used the parsonage for five years as the new structure was being constructed. Finally, in 1970, the building was completed, and the congregation entered into its new structure, the same one that is used today.

During this time of demolishing and building, the congregation continued to fellowship and worship with services being held at the church’s parsonage, located at the end of 11th Street in the Hill community. Under the direction of Pastor Brown, a builder himself, the members used the parsonage for five years as the new structure was being constructed. Finally, in 1970, the building was completed, and the congregation entered into its new structure, the same one that is used today.

The Friendship Missionary Baptist Church has been an important contributor to the Hill Community, the City of Apalachicola, and the County of Franklin since its inception, and continues its legacy of service to our God and service to His children. During these years of service, three buildings have housed the congregation: the initial rented structure on the corner of 8th Street and Avenue L where the fledgling band met after leaving Mount Zion, their first structure which was built, damaged, and rebuilt on the site of the current location on 9th Street between Avenue L and Avenue M, and finally the current brick structure, built following the destruction of the fire-ravaged and repaired wooden structure.

During the mid-90s, the Friendship Family adopted its motto: “You always have a friend at Friendship!” This phrase was created by member, Sis. Keeva Gatlin, and continues to be the signature statement for the church, boldly proclaimed throughout the community, just as the members boldly proclaim that we have a friend in Jesus.

From the days of its humble beginning in 1904, a small assemblage of believers, to the present, a strong congregation of servants, the Friendship pulpit has been home to twelve (12) spiritual leaders. These twelve men of the Gospel, listed below, were each charged with a calling to fulfill, that of teaching and guiding, preaching and healing, saving and serving, as they continued their work on the battlefield, doing their Master’s Will, sharing the mighty Word with their parishioners and winning souls for the Lord.

Past Pastors Include: 1904--1906: Minister Byrd (not an official church), 1906--1906: Pastor J. C. Sapp, 1906--1916: Pastor N. A. Tillman, 1916--1918: Pastor Webb, 1918--1923: Pastor Hopkins, 1923--1930: Pastor Maine, 1930--1965: Pastor D. F. Battles, 1965--1971: Pastor Christopher Brown 1971--1974: Pastor John R. Bowers, 1974--1994: Pastor George Waddell, 1994--1999: Pastor Johnny Curry, 1999--present: Pastor James Williams

In reflecting on the rich and distinct heritage of the Friendship Missionary Baptist Church, we are reminded of the goodness of our Heavenly Father and give thanks to Him for His many blessings, down through these years. As we reminisce on our illustrious past in our preparations for embarking on future journeys, we shall continuously seek out and listen to the wisdom imparted from our elders, following the words of Moses who advised us in Deuteronomy 32:7 to always “Remember the days of old”. We must also make efforts to nurture our union as a church family, for “The body is a unit, though it is made up of many parts; and though all its parts are many, they form one body,” words from a letter written by the Apostle Paul in 1 Corinthians 12:12.

Just as those original eight Christians united together in 1904 and through their faith in God, established a bond that has now withstood more than a centennial of moments, the Friendship Family, under the leadership of our anointed spiritual leader, Pastor James Williams, continues to dedicate our hearts, our souls and our labors to maintaining and growing our church’s ministry, doing such as one Body united in love; love for our Heavenly Father, for each other and for each of you, holding true to our motto . . .

“You always have a friend . . . at Friendship!”

This history was written by Sis. Elinor Mount-Simmons, Church Secretary/Clerk, in collaboration with Deacon Noah Lockley, Sr., Church Historian (deceased 2020). Additional historical references were contributed by members: Mother Katie Bell (deceased 2011), Deacon Clarence Williams (deceased November 2015) and Mother Willie Williams, with assistance from Sis. Sarah Mount of First Mount Moriah Baptist Church (Panama City). Scriptural references were supplied by Pastor James Williams and Sis. Mount-Simmons.

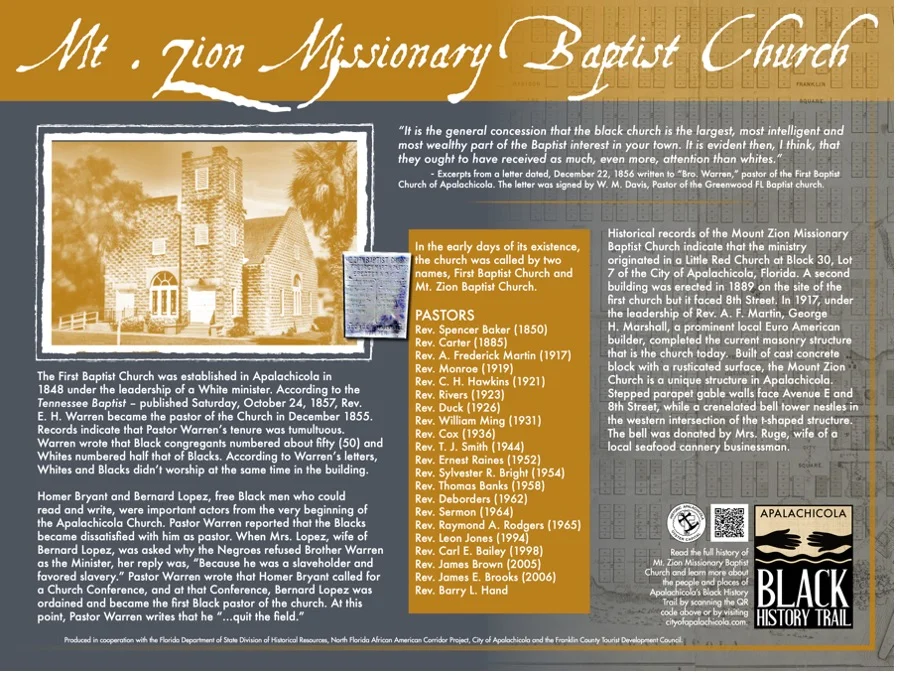

Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church

Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church

In the early days of its existence, this church, located at the corner of Highway 98 and 7th Street, was called by two names, First Baptist Church and Mt. Zion Baptist Church. The First Baptist Church was established in Apalachicola in 1848 under the leadership of a White minister. According to the Tennessee Baptist – published Saturday, October 24, 1857, Rev. E. H. Warren became the pastor of the Church in December 1855. The 1857 publication indicates that Pastor Warren’s tenure at the Apalachicola church was tumultuous. Warren wrote that Black congregants numbered about fifty (50) and Whites numbered half that of Blacks. Warren also noted that the house occupied as property for the Church was owned by the Negroes. According to Warren’s letters, Whites and Blacks didn’t worship at the same time in the building.

Homer Bryant and Bernard Lopez, free Black men who could read and write, were important actors from the very beginning of the Apalachicola Church. Pastor Warren reported that he found the Blacks becoming dissatisfied with him as the pastor. When Mrs. Lopez, wife of Bernard Lopez, was asked why the Negroes refused Brother Warren as the Minister, her reply was, “Because he was a slaveholder and favored slavery.”

A letter dated, December 22, 1856, was written to “Bro. Warren”, pastor of the First Baptist Church of Apalachicola. The letter was signed by W. M. Davis, Pastor of the Greenwood FL Baptist church. The letter begins: “When I say that many spirits suffer depression on account of the state of things in the Apalachicola Church, I but say what is painfully true. I think I can say in truth that a majority of the most prominent members of the W. F. Association are deeply grieved at the result of what we must regard as unfortunate management in your church affairs. We do not believe that there are, considering their opportunities, two members more worthy among you than Homer and Bernard.”

The letter continues: “If you exclude Homer and Bernard, I fear the prospects of the blacks are ruined henceforth, ad infinitum. It is the general concession that the black church is the largest, most intelligent and most wealthy part of the Baptist interest in your town. It is evident then, I think, that they ought to have received as much, even more, attention than whites.”

Pastor Warren wrote that Homer Bryant called for a Church Conference, and at that Conference, Bernard Lopez was ordained. At this point, Pastor Warren writes that he “…quit the field”.

Historical records of the Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church indicate that the ministry originated in a Little Red Church at Block 30, Lot 7 of the City of Apalachicola, Florida. The Church was erected under the leadership of Rev. Spencer Baker, and later, Rev. Martin. It was documented in Church records that in 1880, Sister Jency Davis attended Sunday School in the “Little Red Church”.

Historical records of the Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church indicate that the ministry originated in a Little Red Church at Block 30, Lot 7 of the City of Apalachicola, Florida. The Church was erected under the leadership of Rev. Spencer Baker, and later, Rev. Martin. It was documented in Church records that in 1880, Sister Jency Davis attended Sunday School in the “Little Red Church”.

A second building was erected in 1889 on the site of the first church but it faced 8th Street. Both the 1848 and the 1889 buildings were wooden structures. A 1939 Work Progress Administration Historical Records Survey Church Inventory Form indicates that the first Black clergyman at Mount Zion church was Benjamin Lopierce. Given what is learned from the documents from Brother Warren, Benjamin Lopierce could be Bernard Lopez. Mount Zion Church records indicate that Rev. Spencer Baker, arrived at the Church in the 1850s and served the congregation during the period after the Civil War until the 1880s.

In 1917, under the leadership of Rev. A. F. Martin, George H. Marshall, a prominent local Euro American builder, completed the current masonry structure that is the church today. Built of cast concrete block with a rusticated surface, the Mount Zion Church is a unique structure in Apalachicola. Stepped parapet gable walls face Avenue E and 8th Street, while a crenelated bell tower nestles in the western intersection of the t-shaped structure. The bell was donated by Mrs. Ruge, wife of a local seafood cannery businessman. Members of the Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church Trustee Board in 1917 were Benjamin Bryant, Chairman, Thomas Cook, Secretary, W. M. Armstead, Treasurer, James B. Bates, and Will Moore. Deacon Board Members were E. M. Spencer, William E. Jones, Chairman, L. W. Bryant, and W. G. Griggs.

Unlike the other churches built in Apalachicola during the first two decades of the twentieth century, the main windows in the Mt. Zion Church are Roman arched, not Gothic. The structure was rehabilitated in 1988 and 2001 with financial assistance from the Florida Department of State. The building was heavily damaged during the 2018 Hurricane Michael and is currently being repaired thanks to a 2021 grant from the Florida Department of State Division of Historical Resources.

Early Pastors include: Rev. Spencer Baker (1850), Rev. Carter (1885), Rev. A. Frederick Martin (1917), Rev. Monroe (1919), Rev. C. H. Hawkins (1921), Rev. Rivers (1923), Rev. Duck (1926), Rev. William Ming (1931), Rev. Cox (1936), Rev. T. J. Smith (1944), Rev. Ernest Raines (1952), Rev. Sylvester R. Bright (1954), Rev. Thomas Banks (1958), Rev. Deborders (1962), Rev. Sermon (1964), Rev. Raymond A. Rodgers (1965), Rev. Leon Jones (1994), Rev. Carl E. Bailey (1998), Rev. James Brown (2005), Rev. James E. Brooks (2006), Rev. Barry L. Hand.

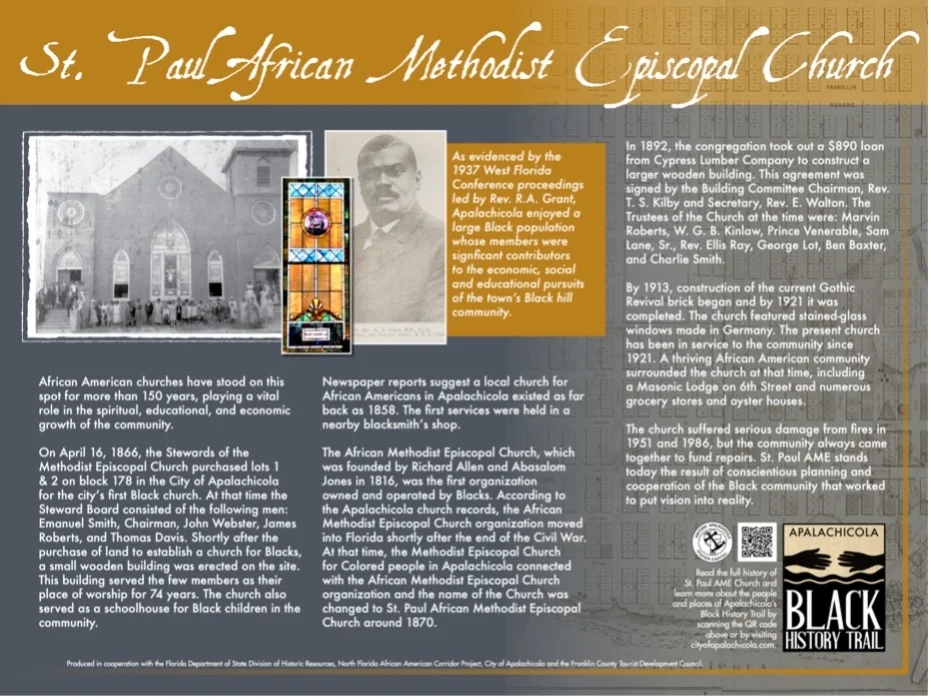

St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church

St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church

African American churches have stood on this spot for more than 150 years, playing a vital role in the spiritual, educational, and economic growth of the community.

On April 16, 1866, the Stewards of the Methodist Episcopal Church purchased lots 1 & 2 on block 178 in the City of Apalachicola for the city’s first Black church. At that time the Steward Board consisted of the following men: Emanuel Smith, Chairman, John Webster, James Roberts, and Thomas Davis. Shortly after the purchase of land to establish a church for Blacks, a small wooden building was erected on the site. This building served the few members as their place of worship for 74 years. The church also served as a schoolhouse for Black children in the community.

Newspaper reports suggest a local church for African Americans in Apalachicola existed as far back as 1858. The first services were held in a nearby blacksmith’s shop.

The African Methodist Church, which was founded by Richard Allen and Absalom Jones. The organization moved into the South shortly after the Civil War. Prior to the end of the Civil War, since most Blacks living in the South labored under their owners, the organization could not make great inroads in the South during the period of enslavement.

An excerpt from the Quadrennial Address of the Bishop of the A.M.E. Church to the General Conference of 1864 underscores the high premium the A.M.E. organization placed on education: “We assure you…this is no time to encourage ignorance and mental sloth; to enter the ranks of the ministry, for the education and elevation of millions now issuing out of the house of bondage, require men, not only talented, but well educated; not only well educated, but thoroughly sanctified unto God.”

According to the Apalachicola Church records, the African Methodist Church did move into Apalachicola in 1867. At that time, the Methodist Episcopal Church for Colored in Apalachicola connected with the African Methodist Church organization and the name of the Church was changed to St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church around 1870, and a Parsonage was built next door in 1882. In 1868, the first choir was organized at St. Paul A.M.E. under the direction of William Decker Johnson, a noted musician from the North who came to Apalachicola to organize the choir.

On December 4, 1892 the congregation took out a $890 loan from Cypress Lumber Company to construct a larger wooden building. This agreement was signed by the Building Committee Chairman, Rev. T. S. Kilby and Secretary, Rev. E. Walton. The Trustees of the Church at the time were: Marvin Roberts, W. G. B. Kinlaw, Prince Venerable, Sam Lane, Sr., Rev. Ellis Ray, George Lot, Ben Baxter, and Charlie Smith (brother of Emanuel Smith).

Always striving to do a little more or to go a little further, the congregation was not contented with the little wooden church on the corner. They had a vision for something magnificent. Something that was more in keeping with the idea of providing something better for those who would come after them. Under the leadership of Rev. J. M. Wise, the members started to acquire funds for the construction of the current Church. Some of the officers at the time were Rev. W. W. “Bill” Collins, W. M. Richardson, Spartan Jenkins, Frank Taylor, Simon “Scase” Johnson, and Elijah Taylor. Sometime during the year 1913, Bro. Simon “Scase” Johnson offered the motion to build the Church as it stands today. These leaders were the visionaries for the Gothic Revival brick church, which began in 1913 and was completed in 1921. The stained-glass windows were made in Germany.

The present church has been in service to its member and community sine 1921. A thriving African American community surrounded the church at that time, including a Masonic Lodge on 6th Street and numerous grocery stores and oyster houses.

In 1937, the 32nd Annual Session of the West Florida Conference of the African Methodist Church was held in River Junction, Florida with the Right Reverend R. A. Grant, LL.D., Presiding Bishop. Reverend J. H. Tunsell was Pastor of St. Paul A.M.E. at the time. The conference records indicate that the following members of St. Paul A.M.E. contributed financially to the conference: T. E. Gaines, H. D. Lane, Jessie Lane, J. I. Logan, Mary Roberts, Nancy McGee, W. L. Calloway, Lucy Gavins, George Johnson, Prof. Hall, Hood Lee, Mat Rayford, H. L. Howe, Elizabeth Goodson, Sallie Tallie, Ella Johnson, Charlie Mitchell, Rosa T. Williams, W. T. Allen, Wash Mitchell, N. V. Green, Johnnie Crooms, Norah Rainey, Louise Felton, Hattie Abram, Ruby Tampa, Frank Taylor, J. H. Glynn, George H. Wynn, Sarah Mitchell, Sid Hawkins, P. H. Foster, Willie M. Sweet, A. M. Gavins, Rochell Crooms, Hood Lee, Seth Walton, Minnie Simmons, W. M. Richard, Isaiah Abram, Augusta Capers, Lessie Foster, Mary Lemons, Carrie Lewis, Josephine Simpson, Mary Grace, Manervina Williams, Mandy Allen, James Edwards, M. E. Calvary, Viola Gaines, Ella Butler, Hagger Pope, Minnie Humphries, Rosa L. Rodgers, Bettie Tunsell, E. R. Robertson, Willie Herd, Odeal Speed, Jacy Clay, Retta Speed, Chester Rhodes, Lottie Rhodes, H. D. Lane, W. W. Campbell, J. I. Hogan, S. W. Johnson, Chancy Woods, Gertrude Green, Maude Collins, Amos Lemons, Ruffin Rhodes, Mary J. Barfield, Dora Druce, Nettie Cooper, Geardine Edwards, Giles Smith, Dave Johnson, Eva O’Neal, Rita Perkins, Ellen Jackson, Sadie Feed, Patience Jackson, J. H. Ekles, W. L. Calvary, Herman Gray, T. Louise Simmons, M. J. Eckles, Addie Riser, Frances Riser, Lee Perkins, Mamie James, Albert James, Julia Safore, Julia Love, Annie Murphy, Rebecca Thorton, Rebecca Martin, Mamie Davis, P. A. Collins, Pearl Feed, Julius Buchanan, Sallie Walton, Jennie Cook, Anna Ingram, Emma L. Rhodes, S. Jenkins, Carrie Clark, Olivia Blakley, Rubin Safore, Navin Roberts, James Freeman, Eva Smith, M. J. Walton, Evins Rhodes, Elijah Hawkins, Ella Louise Williams, W. M. Ziegler, Lizzie Elliott, Willie Tampa, Ben Tamps, Charlie Britt, Julia Cobb, N. B. Holmes, Reginald Clark, and R. C. Fortune.

In 1937, the 32nd Annual Session of the West Florida Conference of the African Methodist Church was held in River Junction, Florida with the Right Reverend R. A. Grant, LL.D., Presiding Bishop. Reverend J. H. Tunsell was Pastor of St. Paul A.M.E. at the time. The conference records indicate that the following members of St. Paul A.M.E. contributed financially to the conference: T. E. Gaines, H. D. Lane, Jessie Lane, J. I. Logan, Mary Roberts, Nancy McGee, W. L. Calloway, Lucy Gavins, George Johnson, Prof. Hall, Hood Lee, Mat Rayford, H. L. Howe, Elizabeth Goodson, Sallie Tallie, Ella Johnson, Charlie Mitchell, Rosa T. Williams, W. T. Allen, Wash Mitchell, N. V. Green, Johnnie Crooms, Norah Rainey, Louise Felton, Hattie Abram, Ruby Tampa, Frank Taylor, J. H. Glynn, George H. Wynn, Sarah Mitchell, Sid Hawkins, P. H. Foster, Willie M. Sweet, A. M. Gavins, Rochell Crooms, Hood Lee, Seth Walton, Minnie Simmons, W. M. Richard, Isaiah Abram, Augusta Capers, Lessie Foster, Mary Lemons, Carrie Lewis, Josephine Simpson, Mary Grace, Manervina Williams, Mandy Allen, James Edwards, M. E. Calvary, Viola Gaines, Ella Butler, Hagger Pope, Minnie Humphries, Rosa L. Rodgers, Bettie Tunsell, E. R. Robertson, Willie Herd, Odeal Speed, Jacy Clay, Retta Speed, Chester Rhodes, Lottie Rhodes, H. D. Lane, W. W. Campbell, J. I. Hogan, S. W. Johnson, Chancy Woods, Gertrude Green, Maude Collins, Amos Lemons, Ruffin Rhodes, Mary J. Barfield, Dora Druce, Nettie Cooper, Geardine Edwards, Giles Smith, Dave Johnson, Eva O’Neal, Rita Perkins, Ellen Jackson, Sadie Feed, Patience Jackson, J. H. Ekles, W. L. Calvary, Herman Gray, T. Louise Simmons, M. J. Eckles, Addie Riser, Frances Riser, Lee Perkins, Mamie James, Albert James, Julia Safore, Julia Love, Annie Murphy, Rebecca Thorton, Rebecca Martin, Mamie Davis, P. A. Collins, Pearl Feed, Julius Buchanan, Sallie Walton, Jennie Cook, Anna Ingram, Emma L. Rhodes, S. Jenkins, Carrie Clark, Olivia Blakley, Rubin Safore, Navin Roberts, James Freeman, Eva Smith, M. J. Walton, Evins Rhodes, Elijah Hawkins, Ella Louise Williams, W. M. Ziegler, Lizzie Elliott, Willie Tampa, Ben Tamps, Charlie Britt, Julia Cobb, N. B. Holmes, Reginald Clark, and R. C. Fortune.

The list of contributors to the 1937 West Florida Conference is evidence of a substantial congregation, which indicates a sizeable Black population in Apalachicola. In addition, the members listed were also significant contributors to the economic, social, and educational pursuits of Black people on the Hill.

The St. Paul AME Church suffered serious damage from 1951 and 1986 fires, but the community always came together to fund repairs. The damages caused by both fires were very extensive. The insurance coverage was certainly helpful in restoring the building to its original historical beauty. Yet, it was not enough to cover the repairs needed.

The members of the church put their personal financial resources together to bring the building back to its original state. Although this effort was well received, it was not enough for the job. Therefore, money raising drives were implemented to help provide additional funds that were needed. Through the extra effort of the members and the outstanding assistance of the local citizens of the community and the local lending institutions, funds were provided to complete the job. The building’s roof was damaged by the 2018 Hurricane Michael. Since then, the building has been repaired thanks to a 2021 grant from the Florida Department of State Division of Historical Resources.

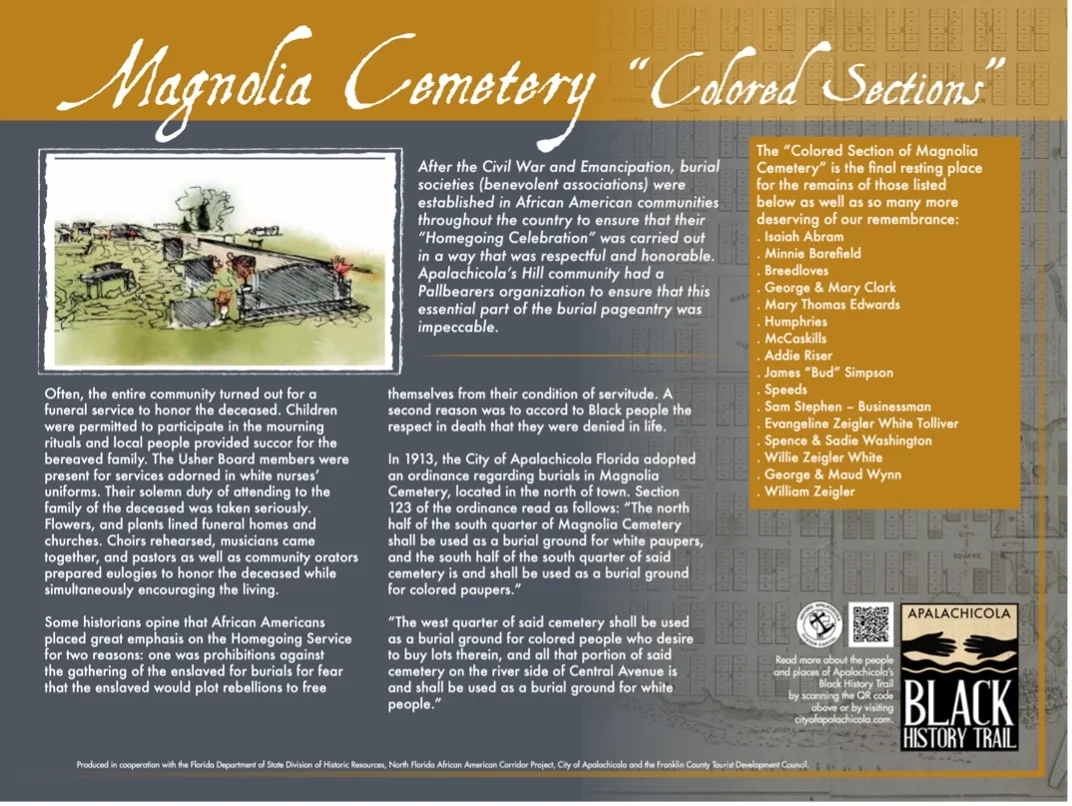

Magnolia Cemetery “Colored Sections”

Magnolia Cemetery “Colored Sections”

After the Civil War and Emancipation, burial societies (benevolent associations) were established in African American communities throughout the country, and especially in the south. African American people paid small weekly/monthly dues to ensure that their “Homegoing Celebration” (funeral) was carried out in a way that was respectful and honorable. Apalachicola’s Hill community had a Pallbearers organization to ensure that this essential part of the burial pageantry was impeccable. Funeral homes and their owners were respected members of the community.

Often, the entire community turned out for a funeral service to honor the deceased. Children were permitted to participate in the mourning rituals and local people provided succor for the bereaved family. The Usher Board members were present for services adorned in white nurses’ uniforms. Their solemn duty of attending to the family of the deceased was taken seriously.

Flowers, and plants lined funeral homes and churches. Choirs rehearsed, musicians came together, and pastors as well as community orators prepared eulogies to honor the deceased while simultaneously encouraging the living.

Some historians opine that African Americans placed great emphasis on the Homegoing Service for two reasons: one was prohibitions against the gathering of the enslaved for burials for fear that the enslaved would plot rebellions to free themselves from their condition of servitude. A second reason was to accord to Black people the respect in death that they were denied in life.

In 1913, the City of Apalachicola Florida adopted an ordinance regarding burials in Magnolia Cemetery, located in the north of town. Section 123 of the ordinance read as follows: “The north half of the south quarter of Magnolia Cemetery shall be used as a burial ground for white paupers, and the south half of the south quarter of said cemetery is and shall be used as a burial ground for colored paupers.”

In 1913, the City of Apalachicola Florida adopted an ordinance regarding burials in Magnolia Cemetery, located in the north of town. Section 123 of the ordinance read as follows: “The north half of the south quarter of Magnolia Cemetery shall be used as a burial ground for white paupers, and the south half of the south quarter of said cemetery is and shall be used as a burial ground for colored paupers.”

“The west quarter of said cemetery shall be used as a burial ground for colored people who desire to buy lots therein, and all that portion of said cemetery on the river side of Central Avenue is and shall be used as a burial ground for white people.”

The “Colored Section of Magnolia Cemetery” is the final resting place for the remains of those listed below as well as so many more deserving of our remembrance: Isaiah Abram , Minnie Barefield, Breedloves, George & Mary Clark, Mary Thomas Edwards, Humphries, McCaskills, Addie Riser, James “Bud” Simpson, Speeds, Sam Stephen – Businessman, Evangeline Zeigler White Tolliver, Spence & Sadie Washington, Willie Zeigler White, George & Maud Wynn, William Zeigler.

Snow Hill Cemetery

Snow Hill Cemetery

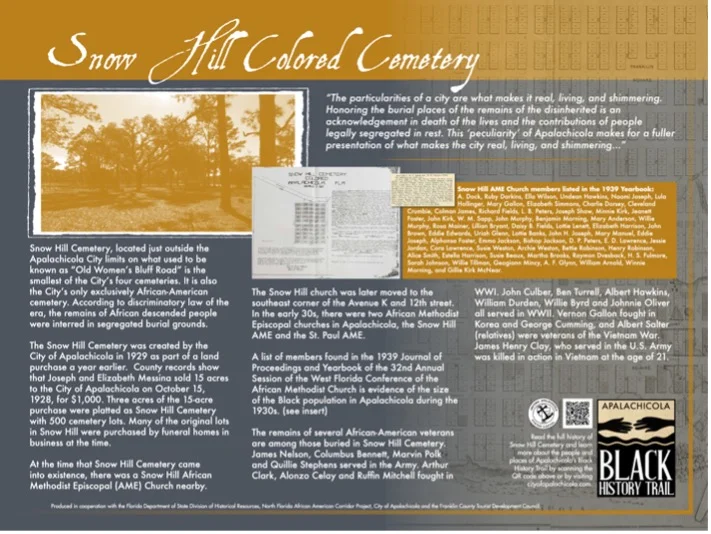

Snow Hill Cemetery is located just outside the Apalachicola City limits on what used to be known as “Old Women’s Bluff Road” and is the smallest of the City’s four cemeteries. It is also the City’s only exclusively African-American cemetery. According to law of the era, the remains of African descended people were interred in segregated burial grounds.

The Snow Hill Cemetery was created by the City of Apalachicola in 1929 as part of a land purchase a year earlier. County records show that Joseph and Elizabeth Messina sold 15 acres to the City of Apalachicola on October 15, 1928, for $1,000. Three acres of the 15-acre purchase were platted as Snow Hill Cemetery with 500 cemetery lots. Many of the original lots in Snow Hill were purchased by funeral homes in business at the time.

At the time that Snow Hill Cemetery came into existence, there was a Snow Hill African Methodist Episcopal Church nearby. The Snow Hill church was later moved. By the early 30s, there were two African American churches in Apalachicola, the Snow Hill AME and the St. Paul AME. A list of members found in the 1939 Journal of Proceedings and Yearbook of the 32nd Annual Session of the West Florida Conference of the African Methodist Church is evidence of the size of the Black population in Apalachicola during the 1930s.

Several African-American veterans are among those buried in Snow Hill Cemetery. James Nelson, Columbus Bennett, Marvin Polk and Quillie Stephens served in the Army. Arthur Clark, Alonzo clay and Ruffin Mitchell fought in WWI. John Culber, Ben Turrell, Albert Hawkins, Willia Durden, Willie Byrd and Johnnie Oliver all served in WWII. Vernon Gallon fought in Korea and George Gumming and Albert Salter were veterans of the Vietnam War. James Henry Clay, who served in the U.S. Army, was killed in action in Vietnam at the age of 21.

Snow Hill AME Church members listed in the 1939 Yearbook are: A. Dock, Ruby Dawkins, Ella Wilson, Undean Hawkins, Naomi Joseph, Lula Hollinger, Mary Gallon, Elizabeth Simmons, Charlie Dorsey, Cleveland Crumbie, Colman James, Richard Fields, L. B. Peters, Joseph Shaw, Minnie Kirk, Jeanett Foster, John Kirk, W. M. Sapp, John Murphy, Benjamin Morning, Mary Anderson, Willie Murphy, Rosa Mainer, Lillian Bryant, Daisy B. Fields, Lottie Lenett, Elizabeth Harrison, John Brown, Eddie Edwards, Uriah Glenn, Lottie Banks, John H. Joseph, Mary Manuel, Eddie Joseph, Alphonsa Foster, Emma Jackson, Bishop Jackson, D. P. Peters, E. D. Lawrence, Jessie Jordan, Cora Lawrence, Susie Weston, Archie Weston, Bettie Robinson, Henry Robinson, Alice Smith, Estella Harrison, Susie Beaux, Martha Brooks, Raymon Dvesback, H. S. Fulmore, Sarah Johnson, Willie Tillman, Geogiann Mincy, A. F. Glynn, William Arnold, Winnie Morning, and Gillie Kirk McNear.